I went to see Pulp at the O2 in June. I’ve listened to Pulp pretty much obsessively ever since. The live show was great, as is the new stuff, but dancing to the likes of Disco 2000 and Babies inevitably made me nostalgic for the 90s.

So extending the trip back in time (to continue a theme from a previous edition of Only Third Party), I also recently re-read John Harris’ book about the Britpop years, The Last Party.

Something that stuck out from this re-read, alongside the utter tabloid mania around the Blur v Oasis chart battle, was the media reaction around Jarvis Cocker running on stage during Michael Jackson’s performance at the 1996 Brit Awards.

According to Harris, The Mirror tried to use the occasion to go after the Pulp frontman, siding with Jackson. They ended up having to change tack pretty quickly, because the wider newspaper narrative was decidedly pro-Jarvis (Michael Jackson was still recovering reputationally from child abuse allegations).

Piers Morgan (in charge of The Mirror at the time) clearly believed in Don Draper’s mantra from season three of Mad Men. Namely, “If you don’t like what’s being said, change the conversation”. Morgan clearly thought he could take the lead and sway the public to his line of thinking - but he overstated his paper’s influence and completely misread the national mood.

In the 2020s, it’s arguable that a concept such as “the national mood” is out of date, so shifting the conversation becomes a potentially moot point. But even if consensus is hard to come by, there are still certain narratives that catch on - even if, like Piers Morgan’s vilification of Jarvis Cocker, their accuracy is a long way off the mark.

For example, the myth of the attention span is one that’s long been hard to shake. It’s now seen as a truism to say something like “our attention spans are shorter than ever” - here it is mentioned in this otherwise interesting article about the average length of pop songs. But there’s limited evidence to suggest that human beings even have such a thing as an “attention span”. The heuristic, however, is just too inviting for media and strategists alike to resist. Apart from me, I will continue to be the old man yelling at clouds about it for the foreseeable.

The more entrenched a heuristic becomes, like the attention span myth, the harder it is to shake. That’s why it worries me to see the rumblings of “AI is already taking entry-level jobs” stories begin to proliferate in a number of outlets.

You can see why this heuristic appeals. Generative AI continues to be the hot new tech, but while it is undoubtedly an exciting technology that feels like magic to use, its deployment still feels relatively bite-sized and piecemeal. Indeed, some CEOs have questioned their investment due to a lack of large-scale impact. Case studies and proof points are in high demand.

So to be able to correlate “the rise of genAI” with “the job market is brutal for entry-level roles” hits all the right notes to keep the enthusiasm on the boil.

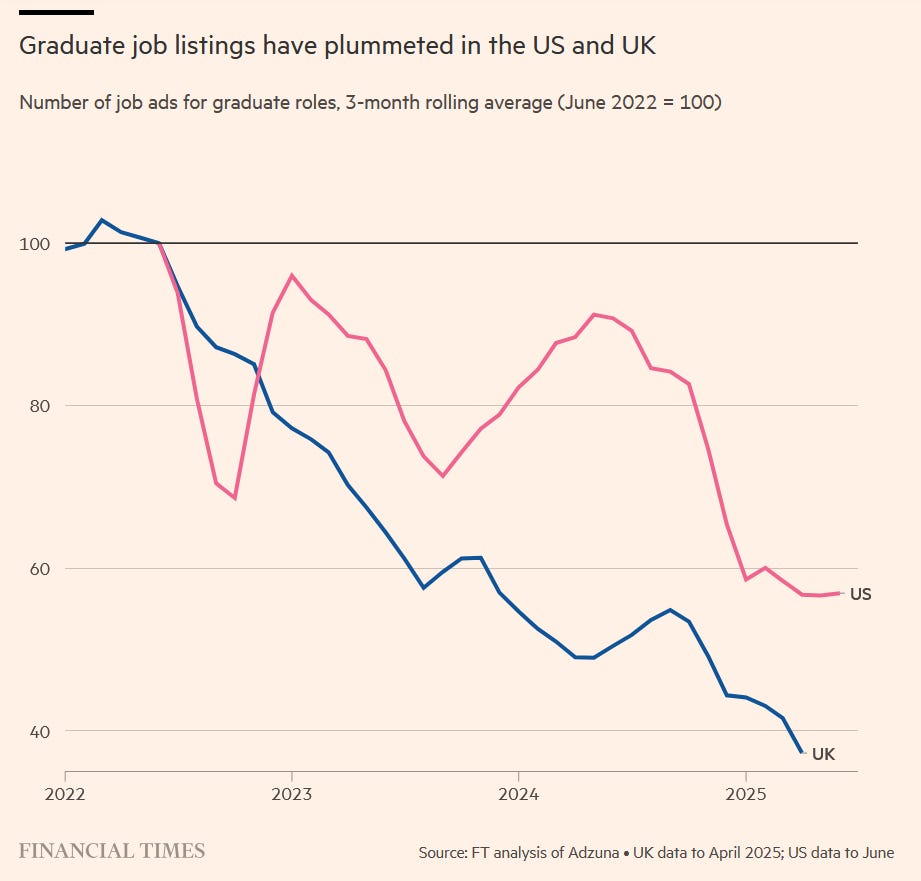

The trouble is, there’s very little proof that deploying generative AI has any meaningful effect on role displacement. That’s according to this analysis in the FT from last week. Looking at the graph of available graduate roles, you can see a clear decline that maps perfectly with the hype around ChatGPT. Except there are also some peaks in the US, and the graph isn’t an absolute number; it’s a relative scale with the maximum set at 2022’s level.

And the deeper analysis speaks to this minimal impact of genAI on jobs. The actual factors involved are the ones affecting other aspects of people’s lives every day - ongoing economic uncertainty, a post-COVID retrenchment (particularly in the tech sector), NICs rises, and no return to historically low interest rates. All your favourite significant, long-term socio-political and economic factors.

But those long-term factors are BORING. GenAI is new and EXCITING. Let’s blame that instead. The trouble with that line of thinking is that heuristics can be powerful.

If it becomes a truism that “AI is taking people’s jobs”, then there may be an expectation among the C-suite that AI SHOULD be taking people’s jobs - even if there’s scant evidence that the current crop of AI software can indeed magically replace people wholesale.

Those overinflated expectations of being able to wave a magic AI wand and cut costs from a business are misplaced. But it’s an attractive narrative. Waving magic wands is fun and easy. Looking into long-term boring systemic factors is boring.

We can see another analogous narrative where a magic wand can fix everything in the demonisation of “algorithms”, or more likely “THE algorithm” that powers whichever big tech platform you think is most evil at the time of writing.

But again, there’s little evidence that those mystical algorithms have any effect on people’s attitudes on a topic. This piece in Asterisk Mag combs through the various scientific studies that have been run on the impact social media has had on political attitudes in the United States.

The answer is simple - the impact is negligible. Issues of polarisation, conspiracy theories and general distrust in institutions are long-standing socio-economic trends. It likely is a truism to say that access to the speed and scale of the internet has made it easier for people who share common views to come together, and brought such views out of the fringes, but the “algorithms make everything worse” narrative lacks any substance.

Truisms, narratives, heuristics - these are fundamental devices to help humans navigate the world. Without them, we’d likely have spent the history of evolution overthinking everything and then getting eaten by a wild beast.

And some truisms have a higher dose of accuracy than others. For example, if you see something on the internet that seems too good to be true, it almost certainly is too good to be true. You probably won’t get rich quickly, become an amazing guitar player overnight, or find lonely singles in your area.

So it is with the “AI has stolen graduate jobs” and “it’s all the algorithms’ fault” narratives - they’re just too simple and blunt to be true. Issues of employment and the cost of doing business are thorny and complex. Any business looking to build communications or campaigns around its approach to recruitment, whether positive or negative, needs to think through these complex, multifaceted factors. The Klarna-style approach of “we’re so cool, we got AI to do it all” is fake news (to deploy another heuristic).

Similarly with the demonisation of algorithms, calling for algorithms to be more transparent or demanding a return to chronological feeds misses the point. People like newsfeeds served to them via algorithms. The whole digital marketing economy is built on such algorithms. Unpacking them and taking them away won’t magically make the world a better place. Campaigning on this kind of platform risks sounding tone deaf and out of touch.

If we want to take Don Draper’s advice and change the conversation, to achieve what Piers Morgan failed to do, we need to avoid getting too carried away by any dominant meta-narrative. Instead, we need to focus on the fundamentals - putting ourselves in the shoes of our target audiences, simplifying our message down to make it memorable, then exploding that message in exciting, creative ways. As a process, it’s simple. Of course, the execution is rarely so simple. But focusing on those fundamentals, and not getting carried away by seductive narratives, generally generates results. That way, to quote Common People, you can feel more confident about burning brightly, instead of endlessly wondering ‘why?’