Back to the media's future

The more our news and media habits change, the more they stay the same

Last weekend, my wife and I revisited the Back to the Future trilogy for the first time in a while. In addition to marvelling that the “future” Marty and Doc Brown visit in number two is actually our past (they go to 2015), we also discussed what it might be like if they remade the movie now.

Based on the original timelines, the 2025 version of Back to the Future would involve its hero travelling back to 1995. Having just seen Pulp at The O2 and relived some of the magic of the Britpop years, I find this idea highly appealing.

One of the repeated tropes in the Back to the Future movies is Marty visiting the town square of Hill Valley in its different eras, marvelling at the differences from his own time. If you were to repeat this exercise for, say, Piccadilly Circus in 1995, I wonder what your immediate, goggle-eyed observations would be?

Clearly, the most obvious one would be a lack of smartphones and a lack of mobile phones in general. The bus fleet would probably stand out, but the cars wouldn’t be that different (especially compared to the 50s jump back).

But 90s haircuts and fashion have been back in style for a while. The music is still incessantly played, and with the likes of Pulp, Oasis, Supergrass and Sleeper all touring this year, you’d arguably feel right at home.

One of the biggest differences would be less noticeable until you picked up a newspaper or switched on the TV. Our attitudes towards social issues, our language, and our inclusivity are significantly different from those of the Nineties.

It is, of course, being an era before the mass adoption of the internet, a completely different media landscape. The only ways to access news were via print and broadcast, and print media was arguably as influential as it has ever been. If you believe the winner’s rhetoric, The Sun were responsible for helping both John Major and Tony Blair win their respective elections.

The story of news and the media in 2025 is nowhere near as straightforward. Where the 90s exemplified centres of power and influence, now we see a landscape of ever-increasing fragmentation and diffuse influence.

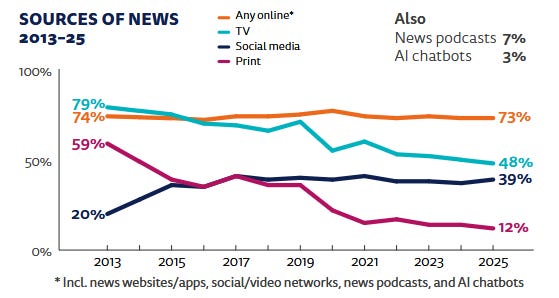

The latest edition of the always-fascinating Reuters Institute Digital News Report paints the latest picture of these tides that have been shifting for many years. We see plenty of new formats and points of influence bubbling up in the research - 3% of respondents use ChatGPT for news, 7% per cent of UK respondents listened to a “news podcast” (a category dominated by The Rest is Politics and BBC Sounds shows), online news consumption remains dominant (although of course not new).

But other trends remain remarkably sticky and resistant to change. Despite its corporate influence waning significantly, X remains a statistically steady source of news for many people. However, while the overall number remains the same, the distinct political swing we’ve seen in MPs using X has been reflected in user behaviour. As ever, binary narratives around “X is dead, long live Bluesky” proved to be wide of the mark.

More worryingly, we see no arrest in the decline of trust in news (at 35%, the UK has one of the lowest global rates of trust in news) or the number of people who actively avoid the news. Again, the UK is near the top of the charts, with 46% of people engaging in some form of news avoidance.

Given these widespread levels of disengagement with news and media, it’s no surprise to see that the UK also has one of the lowest levels of people paying to read their news - 10%. The most popular publications to pay for were The Guardian, The Times and The Daily Telegraph (clearly their “utter woke nonsense” and clickbait social media advertising approach is highly effective).

It all speaks to a landscape where any kind of sense of consensus, as may have been common in the 90s, no matter how illusory it really was, is impossible. It feels like everyone’s talking about Bob Vylan and Kneecap this week, but the data indicates that real people will have only limited knowledge of the whole affair. They’re more likely to have heard about Helen from Wales’ hour of viral TikTok fame.

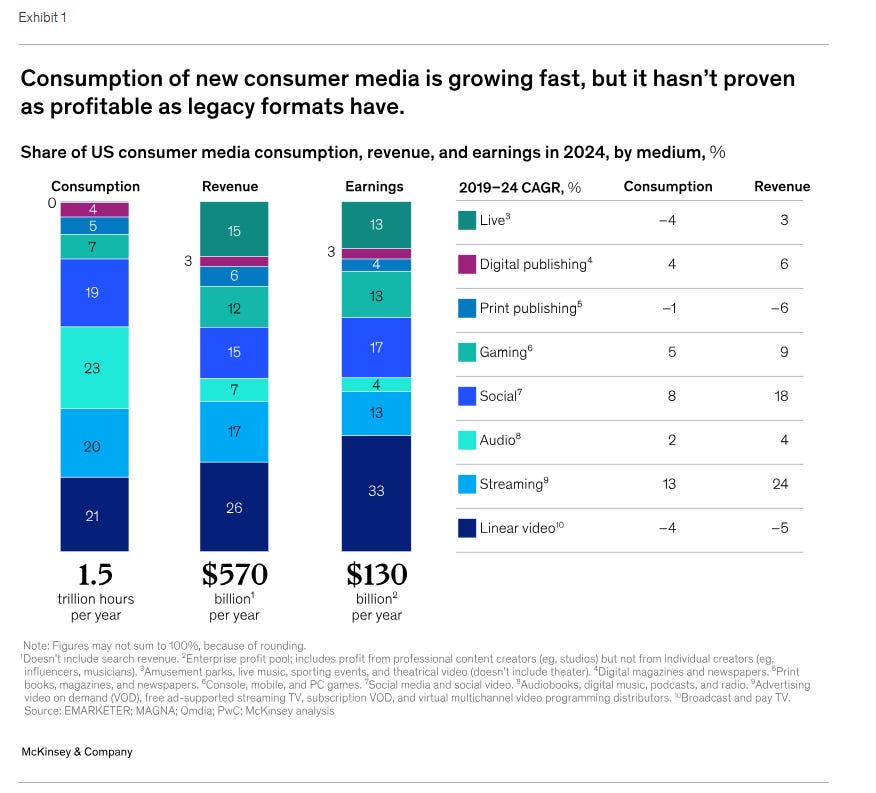

As an outsider, it appears to be a brutally competitive environment for building a media company. There are only a few entrants into the market trying to do that, with the likes of The News Movement and Semafor springing to mind. However, it’s a far cry from the buzzy, PE-backed landscape of the 2010s, when digital media, in particular, felt exciting.

You only have to look at Substack’s journey to find a working example of this media-building struggle. In many ways, Substack represents a bright spark for journalists and writers - many high-profile figures, particularly in the US, but also people like Graham Ruddick and Ian Leslie in the UK, have moved their writing over to Substack. In doing so, they “own” their audience and can run their own paywall, taking in all the revenue after Substack’s cut.

In addition to direct control over their revenue, writers can also exercise their own editorial control, which has its pluses and minuses, particularly when considering the reputational issues Substack faced last year due to its Nazi problem.

But while content moderation and site-wide policies are significant problems for young platforms like Substack, arguably the bigger problem is sustaining growth. And Substack is backed by PE funding at significant valuations, which means that those growth expectations carry some weight.

According to this piece by Anna Marie Cox, the numbers currently appear flimsy and insubstantial. Based on the (admittedly limited) evidence that exists in the public sphere.

“Substack is bringing in about $45M in "annualized revenue"—or their 10 percent cut of the $450M subscribers pay Substack authors. As Byers points out, a $700M valuation would demand Substack’s founders convince investors of a 16x multiple: the kind of math that makes sense for a software company but not a media company.”

And so we get the inevitable, yet unbearably dull, attempts to become more of a “content” platform than simply a newsletter hosting and delivery service.

First, we had Notes, pitched as a Twitter replacement during that period two years ago when it seemed Twitter needed replacing. And now we have “Live” functionality, short-form video, algorithmic recommendations, and a “creator accelerator fund” ($20 million worth of funds, according to Anna Marie Cox). The same old playbook, rinse and repeat.

We know how this plays out, we’ve seen the movie before - creators head over to Substack, posting the same videos as on TikTok and Reels, cashing in on the latest gold rush. They’re followed by the grifters, who work out how to make cash from low-effort, low-quality posts. Then Substack clamps down on that, the money runs out, and we’re left with a Frankenstein’s monster of a platform, lost and confused about its identity (perhaps then time for Bride of Frankenstein, to pursue my analogy to its conclusion).

The bleak, Back to the Future 2 alternative timeline future that Anna Marie Cox suggests is the X path, where “someone with deep pockets [and] interested in culture war influence decides [Substack] has value as a personal ideological playpen”.

But there’s no DeLorean fitted out with a flux capacitor to go back and change the model - even if we knew which point to go back to and tweak.

This is the new media landscape, where new entrants to the market must compete against centuries-old brands with sizeable, loyal fanbases, and also compete against billion-dollar software companies like Meta, who don’t really care what’s on their platforms as long as their users spend their time there.

All we can do as comms people is to stay abreast of the trends, monitor how our audiences consume information, and adjust our plans and campaigns accordingly. And the most important thing is to be as Marty McFly about the process as we can - don’t get stuck in the past. The 90s might be a fun place to visit, but the thinking from that time has had its day.