Scam city

According to Ofcom, many people's faith in their abilitiy to spot scams, fakes and adverts is misplaced.

“What is Facebook these days?” This is a common question we get asked when running digital training across the agency. The stock answer I give is that it’s primarily a utility. Buying and selling products on Marketplace, keeping up with the traffic in your local area on Groups (or maybe that’s just my local Groups). The newsfeed itself is a bit of a wasteland - a swamp of suggested posts, AI-generated slop - oh, and advertising, of course.

Cast your mind back to January of this year; you’ll recall that same newsfeed was the subject of much debate. Mark Zuckerberg did one of his company’s weird hostage videos to announce sweeping changes to how posts would be moderated on the platform. You’d be forgiven for forgetting all about it - despite generating a typically frothy marketing press reaction, very little has changed on Meta’s platforms. The numbers continue to go up, and the advertisers remain in place.

Meta’s platforms may not be exciting or new, having not launched an original, successful product update for many years, but they remain resolutely effective in the eyes of many. Effective for advertisers, particularly start-ups and small businesses. Effective for users, in offering utility across the suite of apps.

However, that effectiveness sadly also applies to scammers as well. The Wall Street Journal published an in-depth report last week on the sheer scale of scam adverts across Meta’s platforms.

According to “an internal analysis” WSJ received access to, “70% of newly active advertisers on the platform are promoting scams, illicit goods or “low quality” products.” An unnamed source from JPMorgan quoted in the article claims that the bank has “repeatedly raised concerns with Meta about its policing of scams.” And while there has been some recent improvement, according to that same source, the sense from the materials WSJ saw indicates that shutting down scams is not a priority for Meta’s senior executives.

This is best evidenced by the number of complaints and red flags advertisers can accrue before getting banned. Again, according to the documentation WSJ accessed, Meta allows advertisers:

“To accrue between eight and 32 automated “strikes” for financial fraud before it bans their accounts. In instances where Meta employees personally escalate the problem, the limit can drop to between four and 16 strikes.”

I’ll admit that I didn’t spend too much time dealing with financial fraud issues when I worked on Meta many years ago, but the punitive measures back then were way more strict than “do it eight times before we consider a ban”. That’s eight people losing their cash to a scam before any action is taken.

And given that we know that these fraud/scam/phishing operations work at scale, with hundreds of different pages and accounts, those eight instances are easily enough to make significant sums of cash before they have to shift tactics.

To be clear here, too, the scammers have to follow the same “pay to play” guidance that we give to brands and businesses. These are paid-for posts across Meta’s platforms. If you were a cynic, you could suggest that Meta profits directly from these scams and fraudulent accounts. That same cynical view suggests it’s not in Meta’s interests to shut down the fraudulent activity too quickly, as it might hurt the bottom line.

Personally, I have some sympathy with Meta when it comes to moderation and policing of its platforms. We’re talking about billions of users and billions of posts. When companies operate at such scale, it’s inevitable that bad actors will be able to profit. Millions of people lose money to fraud in other situations - on the telephone, at cash machines. It’s an unfortunate part of navigating modern life.

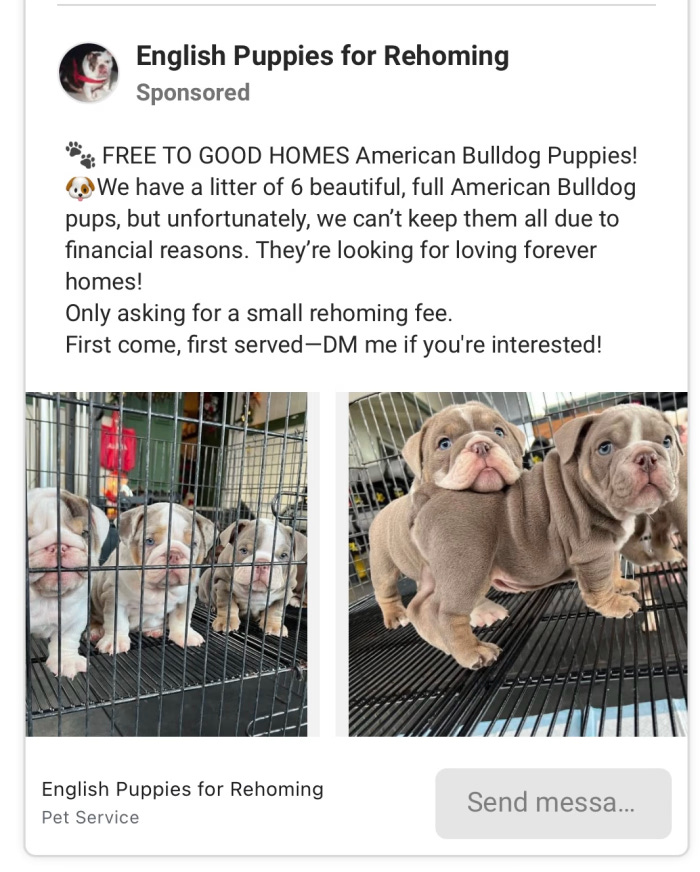

Perhaps, in addition to asking valid questions of Meta about how they simultaneously police and profit from fraud, we need to revisit the topic of media literacy. Many of the examples cited in the WSJ’s report on Meta-based fraud are offers which are simply too good to be true. Puppies available to a good home! Get $75 of power tools for only $9.99! There may have been a time in the early 2010s when Groupon could secure such a bargain. That’s not the case in the inflation-ravaged 2020s.

There’s a distinct gap for a public awareness campaign based on the premise that if something seems too good to be true, and you’ve seen it on Facebook, it definitely IS too good to be true. But perhaps even the notion of running such a campaign is too good to be true.

People don’t want to be educated. We think we know what we’re doing online. We don’t need a nanny state to tell us how to spot something that’s fake or fraudulent. According to Ofcom’s latest Media Use and Attitudes report, 84% of “online adults” in the UK said “they felt confident in judging whether an email, text or online message is potentially a scam”. But 82% also said they felt “confident in recognising advertising online”.

And when the same group was asked to review a series of search results in Google, only 51% correctly spotted that the first four links were sponsored, and that companies had paid for the placement. Equally worrying is that these numbers have gone down year-on-year, and have shown no significant improvement since 2018. The widespread confidence in their ability was misplaced for many people.

It’s also worth noting that “digital natives” (16-24 year olds) scored worse for identifying paid for search links than those over-65. Although perhaps this speaks more to changes in search behaviour, with that cohort being statistically likely to use TikTok as their first port of call, particularly if they’re searching outside of a work environment.

Many of those who failed to notice search advertising (40%) and also failed to spot online scams (14%) fell into the camp that Ofcom describes as “confident but not able”. As in, they rated their abilities to differentiate between different types of posts highly, but failed to follow through on their confidence.

If most people don’t want to be educated, then this particular cohort will probably push back aggressively on the notion.

Dealing with scams and media literacy is a complex, multi-layered and multi-faceted topic. As long as there has been a publicly accessible internet, there have been scams and scammers seeking to take advantage of those unsuspecting, overconfident souls.

Big tech platforms like Meta put their faith in AI and technology to improve their ability to police their platforms. The problem with that is that criminals can also track what platforms do and respond accordingly. The rise of AI may improve policing, but arguably, it can also help make scams and phishing attempts become more sophisticated.

When it comes to looking at the topic through a communications lens, there’s clearly a brand safety angle at play here. Asking questions of companies like Meta about who and what your advertising appears next becomes more important every day.

Also, the scale at which Meta platforms operate, even in the UK, makes increased advertising regulation challenging. But even if Ofcom was able to introduce increased oversight over digital advertising, would the trade-offs be worth it? As Ben Evans regularly points out, the cost of regulation often increases barriers to entry. And as anyone who has ever had to get a video through Comcast approval knows, it’s no mean feat, and may put off start-ups and small businesses.

Perhaps the fatalistic but realistic answer is acceptance, and that the world of online scams is more aligned with that of cybersecurity. And the mantra of cybersecurity is that brands and businesses can and should invest in the strongest levels of protection they can. But even the best defences can be breached when human error (or coercion) gets involved - as we’ve seen with the recent high-profile M&S, Co-op and Harrods examples.

The challenge for Meta, with Facebook in particular, is that if the scams become too prevalent, and the prominent voices like Martin Lewis and Martin Wolf continue to rail against the abuse of their likeness, users may even walk away from using Facebook as a utility. The answer in that scenario to the question “What is Facebook?” is “it’s a scammers scamming each other”.