Intentional attention

If you're feeling stuck in your online habits, perhaps it's time to spend your attention more intentionally

As a parent, you get comfortable with being a liar. Not double Big Mac-sized lies, but little sliders, like “Only Grandma has Cocomelon”. My wife and I find Cocomelon deeply weird, so we concocted this saying to steer Ivy away from it at home. But then, at Grandma’s last weekend, the lie came full circle - “Can I watch Cocomelon? Grandma has Cocomelon”.

Seeing Ivy watching Cocomelon reminded me why we went to such lengths to remove it as an option at home. It puts her in a kind of trance; she seems to be passively watching rather than actively engaging and enjoying it as she does with other shows.

And so we ration Ivy’s exposure to Cocomelon with our mini falsehood. We can do that while she’s young; we’ll eventually come to a point when she sees straight through the lies, a moment when it will also be nigh-on impossible for us to manage her exposure to anything.

Sure, there are tools and settings on phones and tablets to manage access and screen time, but any intelligent teenager can figure out workarounds (that’s part of being a teenager). Besides, adults have those options on their devices, but barely anyone uses them. In fact, I’ve read a slew of pieces recently where the authors feel like they simply can’t turn away from their endlessly updated algorithmic feeds.

In fact, there’s a persistent feeling of being “stuck” emanating from the corners of the internet I frequent. It’s best summed up as a sense that, linked to the “ultra processed content” chat from a few weeks ago, our modern media diets aren’t good for us. But even though we know they aren’t good for us, we find it difficult to change our habits. Like Ivy when she’s watching Cocomelon, we’re lost in something of a trance - and that trance doesn’t make us feel good about ourselves.

Hillary Kelly’s New York Times piece coins the phrase “stucktopia” to try and describe this phenomenon (with heavy reference to four TV shows I’ve not seen - Severance, Fallout, Andor and Silo).

Kelly says, “I’ve felt this inertia and complied with it every time I’ve griped that our attention is constantly co-opted by the affirming banality of social media and meme-sharing, then passed along a dozen memes daily. I know these behaviours are perpetuating my own mental stuckness, but they feel too good to give up.”

It calls to mind one of my favourite pieces of journalism, when Gizmodo challenged one writer to give up each big tech platform (Amazon, Meta, Google, Microsoft, Apple) in turn. Surprisingly (for her and her readers), writer Kashmir Hill reported feeling a perpetual FOMO from not being on Instagram regularly - although that was pre-Reels Instagram, an altogether different place.

A similar tone comes through in Roxane Gay’s excellent piece on her experiences using TikTok. I particularly enjoyed it because, as Matt Muir pointed out in Web Curios, the opening sections paint such a vivid picture of the wormholes that TikTok tends to send its users down. The heady mix of humour, voyeurism and tribalism that is both subtly different for everyone, but also collectively similar due to the stylistic conventions and memes of the platform.

But she, too, ends her article with the rumination that “after a while, there is a certain tedium to TikTok. The feast becomes overwhelming. Our taste buds dull.”

All this rumination on our stucktopia and the death of our culture leads to the obvious question - why don’t we stop? If TikTok and Instagram become tedious, why do people return for more?

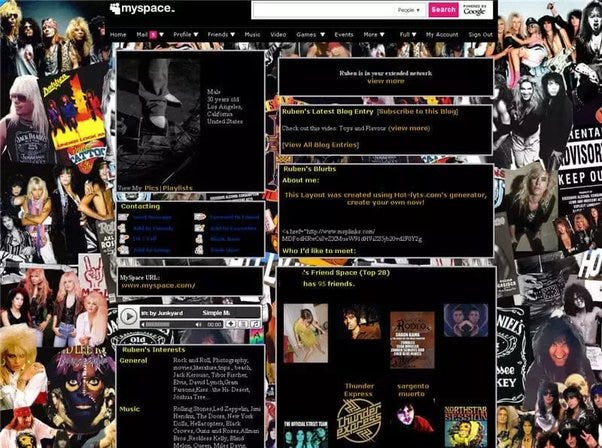

Just because the big platforms of today have been popular for a while, it doesn’t mean they’ll stay compelling forever. When I started working in social, I spent the summer combing Myspace for influencers (we called them slash/slashers back then. As in people who were a DJ/photographer/designer). Then, people moved on as the experience dulled and other alternatives appeared. You can see a similar trend happening right now on Facebook, as the platform becomes a utility over social media.

That summer of Myspace was in 2008. Writing not long after, danah boyd’s talk on "Streams of Content, Limited Attention: The Flow of Information through Social Media" aimed to summarise how and why the new web 2.0 platforms were suddenly taking over. She highlighted four critical factors in (what were then) “new forms of information dissemination”, factors that still hold relevance as we analyse our feelings of “stuck-ness” in 2024. These four points are:

Democratisation - anyone can garner attention, but attention may not be divided equally.

Stimulation - people consume content that stimulates their minds and senses. This, as history tells us, isn’t inherently a good thing.

Homophily - people connect to people like them.

Power - power online is about commanding attention, influencing others' attention, and otherwise trafficking in information. We give power to people when we give them our attention, and people gain power when they bridge between different worlds and determine what information can and will flow across the network (to quote danah boyd verbatim).

boyd’s point about power is particularly relevant when we’re thinking about our potential stucktopia. It can sometimes feel like we’ve forgotten that “we give power to people when we give them our attention”.

And if we give them power when we spend our attention on them, by contrast, we take their power away by being more selective in our attention. It may take time and effort, but it is possible to curate what you see in your feeds and pay attention to online. Most algorithms may be dumb, but you can still help train them by hiding posts you don’t like (you just might need to do it a few times, like me blocking those insufferable Huel adverts on YouTube).

But while it may seem easy to be more selective in how we spend our attention, it’s not so easily done in practice. FOMO definitely plays a part, linked to danah boyd’s point around “homophily” and Kashmir Hill’s experience of giving up Instagram. We’re a social species, we want to know what’s going on in the world so we don’t feel out of touch in our workplaces and group chats. And that sometimes means spending attention on topics we might not have done otherwise.

There’s also little indication that a critical mass of people share any of these “stuck” feelings. I’ve seen it propagate around the specific corners of the internet I frequent (mainly text-based email newsletters). Looking beyond my bubble into the real world shows that the stucktopia is still potentially a minority feeling (in the UK at least).

Ofcom’s most recent “Adults’ media use and attitudes report” showed that more people were comfortable with their screen time than in the previous twelve months, and more people felt that “online communications platforms” made them feel better about themselves. The only indication that the broader UK public feels they’re living in a stucktopia came from those aged 16-24, 48% of whom felt that “they spent too long on social media” (still a minority view, if only just so).

Most people like their TikTok and Instagram feeds, and feel they get more out of it than they lose when choosing to spend their attention there. Deciding to get lost in the flow of posts and videos is potentially no different to a night in front of the TV.

The framing of danah boyd’s 2009 piece is all around that feeling of “flow”: “To be peripherally aware of information as it flows by, grabbing it at the right moment when it is most relevant and valuable, entertaining or insightful. Living with, in, and around information.”

Living with, in, and around information is undoubtedly different from “traditional” broadcast-oriented media, where you would take in the news, and only news, at specific points in the day. Nightly broadcast news, a daily paper, and on-the-hour radio updates.

In 2009, living in and around the flow of information did feel exciting, new and empowering. But as the past 15 years unfolded, there’s a sense that spending too much time with the flow is exhausting. That being “chronically online” isn’t that good for you.

This isn’t about specific platforms or types of “content” being bad for you, or judging how people spend their leisure time, but about identifying that feeling of “oh, I’ve got five minutes; I’ll just pick up my phone/open a new tab and see what’s going on in the world”. And then finding yourself lost in the flow, unintentionally spending your attention on topics that, if you were making more deliberate choices, you would maybe wouldn’t devote any time to.

Perhaps we’d feel less stuck, less zoned out, if we stepped into the flow with intention rather than distraction. Doing it out of choice, rather than out of habit. Having a purpose for picking up your device, so you don’t feel embarrassed when a friend or family member asks you “what are you doing on your phone?”.

A helpful parenting tip I once read was to downplay the allure of your phone by announcing why you were using it. I’m just putting that song on, or looking up what the traffic’s like on the way to Grandma’s house.

By adding this intention, you make the screen seem less like a box of magical treats and more like a functional device. It puts you firmly in charge of the technology, rather than surfacing that “stucktopia” feeling that the technology is somehow controlling you.

Like any habit, being intentional will take time to get used to - and the reward of feeling good about using your phone intentionally will need to be strong to help it stick. But there’s certainly merit in being more intentional with your attention, of being proactive instead of feeling consistently drained by inertia.

It’s a habit that also doesn’t lend itself to lies, however, no matter how small or well-intentioned they might be. Be honest with yourself about why you’re using your phone or browsing the internet. Sometimes we do need some zoning out time, a little break from our intentional attention. Maybe don’t go for Cocomelon though - Ivy’s Grandma’s house only has so much room after all.