Distinctive culture

Is culture stagnating or are we too close to see the big picture? And how much does the big picture matter?

Alongside a rewatch of The Wire and the final season of Curb Your Enthusiasm, I'm really into the old Top of the Pops episodes currently running on BBC4. In TOTP rerun land, it's the summer of 1995.

That means lots of Britpop, but also slightly unlikely appearances, like Michael Bolton three weeks in a row, doing a terrible song called "Can I Touch You…There?" (rude). There are also SO MANY random dance tracks I've never heard before, with 4-5 random dancers jiving along while the producer behind the record awkwardly bangs a bongo drum in the background.

It's a glorious snapshot of the era: Iron Maiden alongside Janet Jackson, Cast alongside Menswear, TLC every week. And while Michael Bolton and Erasure provide some 80s flavours, the whole thing is distinctively 90s. To anyone who grew up in that time, it couldn't be any other period.

It will take a while to get there (four more '90s years to go), but I'll be intrigued to see if episodes from the '00s have that same distinctive flavour, or if they feel relatively modern. One of my favourite memes sums up how it feels different eras of music play out:

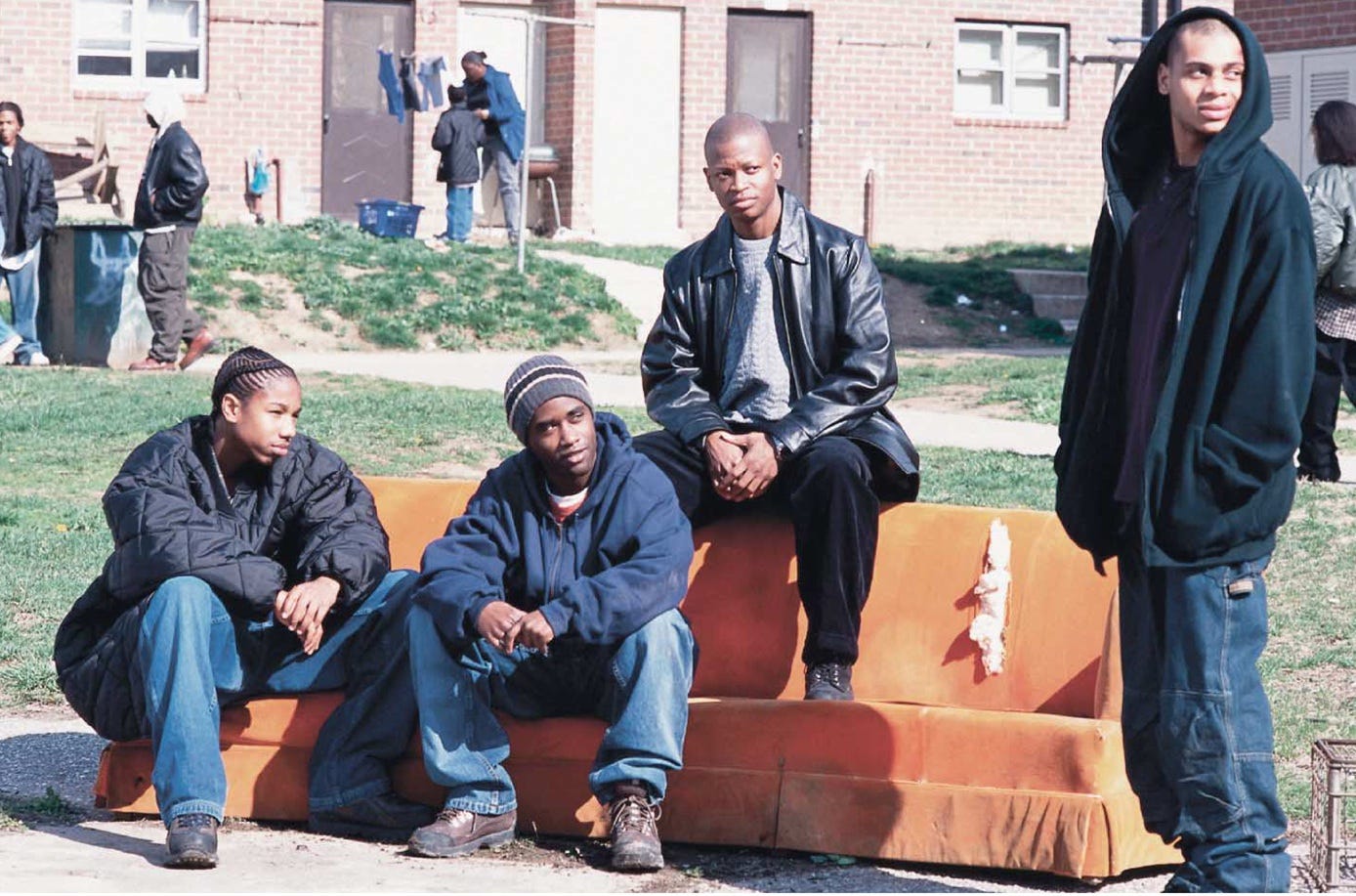

This way of looking back at popular culture doesn’t just apply to music. Case in point: The Wire doesn't feel over 20 years old, even if it is noticeably a "pre-smartphone" show, with a heavy emphasis on pagers in season one. It has flavours of the ‘00s, but doesn’t feel trapped in that era. Shows from the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s felt generally of their time - they looked old even before we got 40 years away from them.

I've been reflecting on this idea of distinctiveness as I read more and more people complaining about the homogeneity and flatness of our modern culture. This ‘crisis of culture’ is nothing new; one of my most re-read pieces of the past five years is called The Big Flat Now. The article's header puts it succinctly: “We regret to inform you that there is no future. Nor is there a past. Music, art, technology, pop culture, and fashion have evaporated as well. There is only one thing left: THE BIG FLAT NOW.”

You might have already come across Ted Gioia’s piece on the state of culture in 2024, which has been widely shared. It was

's thoughts on trend reports and the process of trend forecasting in Contagious that inspired me to write this piece.

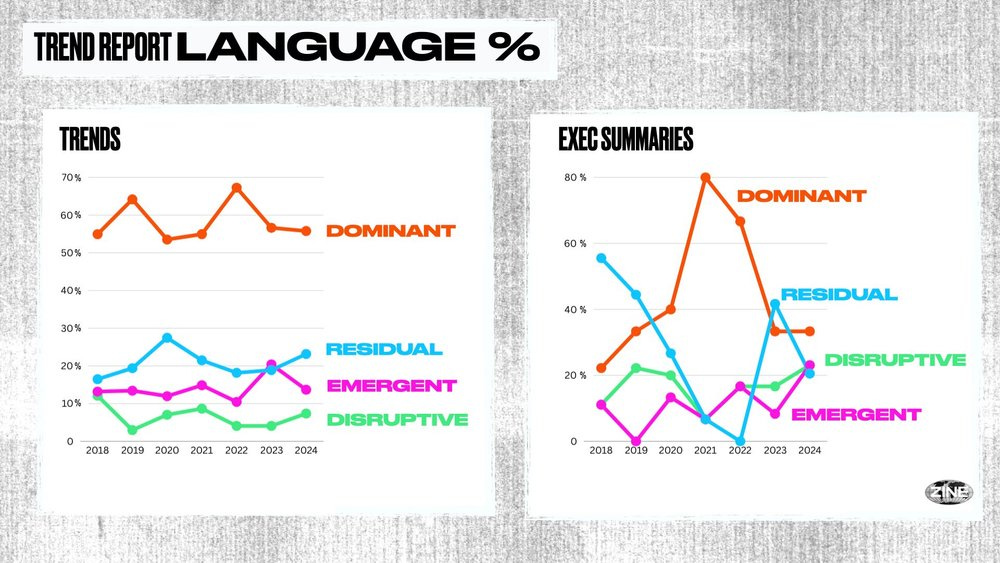

You might be familiar with Matt's work; he creates a meta-trend analysis every year, aggregating 70+ forecasts and trends into a straightforward web page. But Matt went one stage further this year - he analysed the past five years of trend reports to see what they told us about where we are and where we're going in marketing and communications.

The analysis found that most trend reports displayed a widespread lack of novelty and new ideas - trends Matt categorises as "Emergent" or "Disruptive". Most trends showcased were either ubiquitous but fading (Residual) or accepted and now expanding (Dominant). As Matt points out and I've contemplated before, the prevalence of residual and dominant trends could simply be that we should accept that trends don't fit into our annual desire to see something new every December/January. The most noteworthy trends are slower burn and more challenging to notice, but they are no less important for that.

But Matt also argues that the homogeneity of trends reflects a homogeneity of culture. That we're stuck. And you see the evidence of this in the cinema, with films like All Of Us Strangers (which I saw recently and highly recommend) dwarfed by superhero franchises and endless remakes. You see the evidence on TikTok, where the songs from the past have endless second lives, or on Spotify, where algorithmic discovery means you get more of the same of whatever you listen to, with little exploration or deviation. You also see it in the tech that everyone is excited about, with Gen AI purporting to be intelligent when all it does is be, to quote Matt again, "incredible at guessing what should come next based upon the past. It's a tool to usher in our future, yet built upon the average."

There are undoubtedly large kernels of truth in this argument. Our culture does feel different now compared to the early days of smartphones and social media. We read more and more about the difficulty of staying afloat in the creative industries as a mildly successful player. Music, film, media - there are the big players who are dominant enough to turn a profit. There are the small-scale players doing their thing and supporting themselves. But there's no longer a clear path to cross this chasm. Even bands you've heard of now have day jobs. The demise of Vice and Pitchfork shows that online media struggles to survive. The big players dominate the conversation; the smaller players exist in a morass that feels too diffuse to carry any distinctiveness.

But is this lack of distinctiveness many people feel about our culture simply a lack of distance and perspective? Perhaps we're simply too close to what's happening to be able to observe what's truly memorable and notable about the times we're living through. We've been spoilt over the past 20 years (using the birth of Facebook and social media as a convenient yardstick) by the advances we've made in technology. We're used to regular breakthroughs and launches. Now that's tailed off and perhaps returned to the mean, we feel a sense of stasis - when actually that's what normality looks like.

Maybe this technological boom is our distinctiveness, and in five or ten years, when we haven't made the jump to "general AI" (AGI for short) or to self-driving cars, we'll look back and say, "Wow, wasn't that an exciting time to be alive". We'll look back on the era of low-quality, high-engagement clickbait in all its forms with the same "fondness but faint sense of embarrassment" with which we view 90s one-hit wonders or Noel's House Party (younger readers may need to Google that reference).

After all, it's only now that elements of pop culture from the 00s have started to take on some semblance of order and categorisation - to become distinctively 00s. Distinctive enough that you could feasibly do 00s fancy dress in the way you can with other decades.

Indie sleaze caught on as a term, describing the NYC scene documented in the excellent Meet Me In The Bathroom book and documentary. Accompanying indie sleaze is landfill indie, with a more British tone, categorising the glut of post-Libertines indie bands with skinny jeans and deep v-neck t-shirts. You've also got UK garage, emo, and reality TV in all its guises (everything from talent competitions to the semi-scripted likes of The Hills - paving the way for TOWIE in the 2010s). There will be plenty of others - but it feels like it's taken 15 years for these trends to become distinctive enough to be seen in the rearview mirror.

There's no denying, however, that it feels like we're at some kind of crossroads. The rise of Gen AI and its accelerating effect on the seemingly endless sludge of rage bait and engagement bait content across UGC entertainment platforms will prompt some kind of reaction. Maybe that's a gradual drift from those algorithmic feed-based platforms towards a more human-curated digital diet. Or it may be that we'll get hooked on that self-same algorithmically generated, algorithmically served endless stream of videos, only turning our attention away for the nth Batman reboot, starring Mr Beast as Batman.

Whatever shape this immediate future takes, brands and businesses must be prepared to react - while remaining connected to what's happening in audiences' worlds. That means simultaneously monitoring the newer, more exciting trends while paying close attention to the slower-moving, more impactful drivers of behaviour.

Indeed, it may be that we in agency-land see culture as homogenous and flat because it's part of our job to observe what's happening in the world, to define culture for our clients. Our audiences don't care for categorisation - they just want to watch the latest series of The Traitors. Or forget about their lousy day by going into a TikTok wormhole for 30 minutes. Or read Morning Brew for the latest financial news.

Only focusing on the new and emerging risks coming across as out of touch. The best creative work and creative thinking adapts the tried and tested just enough to make it feel fresh and different but not enough to make it alien and unfamiliar. It's a tricky formula, but it's not impossible.

B&Q has brought back their "you can do it when you B&Q it" strapline with a campaign that feels fresh and suitably distinctive. It's the perfect blend of fresh and familiar.

The latest Pot Noodle ad may have offended some people, but it's effective because it has just enough cheekiness and chutzpah for a brand that's always been comfortable in that space. It’s distinctively Pot Noodle. It’s harder to see whether or not it’s distinctively 2020s - but it feels right for right now.

Culture remains a tricky beast to define - Martin Weigel’s piece on this particular c-word remains a touchstone for me on the topic. And the increasing fragmentation of media consumption and the rise of individual FYPs means it’s harder to define than ever - there’s no longer one single culture, if there ever was. That means we need to ensure we’ve got a healthy dose of our audiences’ realities to go with our chin-stroking opinions on the state of the world.

And yes, the summer of 1995 was the summer of Britpop - but it was also a summer when the number one spot went to Michael Jackson (You Are Not Alone), Shaggy (Mr Boombastic) and Simply Red (Fairground). Don’t let the big picture obscure what’s really happening.