Healthy entertainment habits

Some people believe "ultra-processed content" will ruin our brains; but who's to say what's healthy when it comes to entertainment?

I’ve often thought long and hard about living more like Barack Obama. Mainly the way he “routinized” his life by wearing the same things every day. I’m close these days, but I stop short of having multiple versions of the same shirt. I can’t escape the worry that my colleagues will think I’ve not been home and that’s why I’m wearing the same thing.

I probably spend the most time in the morning deciding which trainers to wear. President Obama wouldn’t advise this course of action. He believed in decision fatigue - that you need to save your brain power for the decisions that matter and cut out as many extraneous choices as possible.

Clearly, Obama’s decisions in the Oval Office carry more significance than mine - but decision fatigue is still a principle worth paying attention to. The brain is a muscle; it needs regular rest, just like any other part of your body. One famous research study showed that judges are less likely to rule in favour of a case the closer it is to their allotted break time.

Even if you’re not the POTUS or a presiding judge, you’ll likely have felt mentally worn out at the end of the day. And you may well have soothed your mental burden with some form of entertainment that requires only minimal focus. A movie or TV show you’ve seen before, or something new with an easy-to-follow plot, or the endless algorithmic delights of Instagram, TikTok or YouTube.

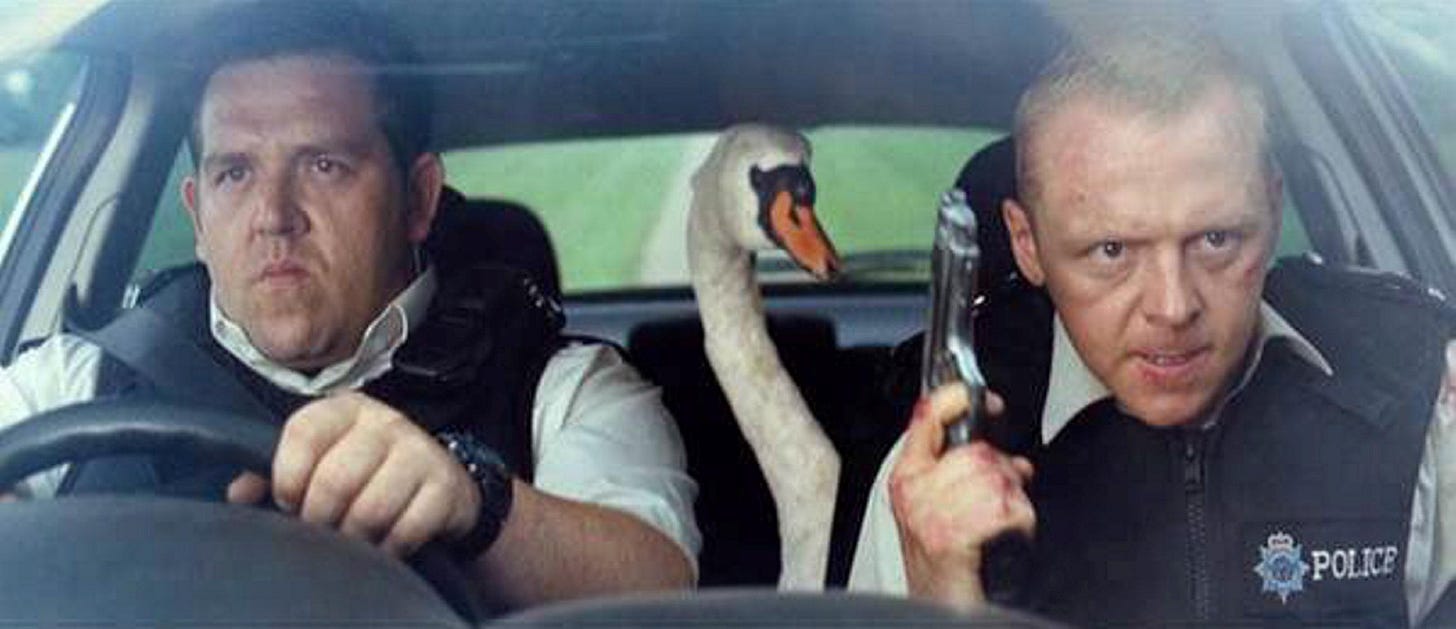

Sometimes, even deciding what to watch on TV in the evening requires a heavy mental lift. There’s too much choice - no wonder we’re statistically likely to stick with what we know or what’s recommended. It’s no different to switching the TV on and watching something because it’s on - arguably the most common pastime before the streaming age took off. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve watched a section of Hot Fuzz just because it’s on (and it’s always on).

There is a growing sense, however, that losing ourselves to recommendation algorithms when we want to relax is unhealthier than time spent passively watching linear TV.

The author of Deep Work, Cal Newport (an excellent book, highly recommend), coined the phrase “ultra-processed content” on his blog, likening algorithmically delivered social posts to ultra-processed foods. Newport sees the similarity in how ultra-processed food and ultra-processed content offer “lab-optimized hyper-palatability”. On the content side, Newport goes on to differentiate between minimally processed content (books and articles), moderately-processed content (radio, television, podcasts, newsletters) and then into ultra-processed content. There’s little definition of ultra-processed content - instead, we get various references to “outraged tweets, aspirational Instagram posts, and aggressively arresting TikToks”.

The most pertinent part of Newport’s classification isn’t which type of media goes into which bucket; that’s a “high culture/low culture” argument that’s as old as time. The most pertinent part of the argument is around the feedback loop creators become trapped in, where they “adapt to what seems to better please the platforms, simplifying and purifying their output to more efficiently feed the algorithms’ goal of hijacking the human desire mechanisms.”

There’s a lot of rubbish in our feeds - it shows up in different forms, depending on the latest trends. There was a significant wave of “you won’t believe what happened…” videos where nothing actually happened. Those AI-generated videos mix what’s trending with stock rubbish to generate cash. There are any number of reactions to reaction videos.

That being said, I still think it’s a big call by Cal Newport to define all social media posts as ultra-processed. Yes, culture might provide informational nutrition (to use the food metaphor), but culture equally - and especially in the case of TV and video platforms - provides entertainment. And it’s no bad thing to want to be entertained, to switch your brain off at the end of a day of decisions and negotiations (especially if those negotiations are with children).

While I may disagree that anything posted on social and video-sharing platforms is the digital equivalent of Doritos (also, I love Doritos), I do think we need a way to accurately describe the different levels of quality we see in our feeds.

Slop is one word that feels like it fits for the low-effort output. To quote Ryan Broderick in Garbage Day, slop “has three important characteristics”. It feels “worthless” to the viewer; it also feels “forced upon us”, that we have to wade through it to get to the good stuff; and finally, it feels “optimised” to be like this. Like an album that’s been phoned in or a pale imitation movie sequel (I have seen all the Friday the 13th movies; that’s a franchise that ended up as slop).

But even as we see the amount of slop in our feeds and culture increase, there is a sense that wading through some slop is almost part of the fun. The rush of finding something worth watching amongst the irrelevant offerings served up by the algorithms is a minor thrill.

But, just as when you get bored of browsing Netflix to find something to watch, is there a point when the wading and the flicking becomes tiresome? Is there a point when we retreat to our favourites, to the short-form social equivalent of watching The US Office again?

Some people argue that the rise of slop and the limited imagination of algorithms will precipitate a return to more curated forms of media. As Matt Muir put it in a recent edition of Web Curios, “We’re doing curation again, it seems”. Whether it’s blogs, Instagram feeds, or short-form videos and Substacks, a common reaction to “there’s too much content” is to focus on selections shortlisted by humans whose taste we admire. The New Yorker piece that celebrates the “new generation of online culture curators” tries to give this new group a name, tentatively suggesting “connoisseurs” as the new label.

The problem with curation is that discovering curators to follow takes time and effort. One of the reasons Twitter users used to drop off after signing up was that they struggled to find people to follow. I remember building my blog feed back in the day - it took a good couple of hours. Most people don't have time for that, particularly if they’ve already filled their quota of decisions.

The TikTok algorithm learns about what you like with impressive speed. Netflix has trending shows and movies to browse. Any attempt to apply a similar lens to curators (select your favourite “connoisseur” from our algorithmically compiled list) falls into the same trap the concept was trying to escape. Curation, whichever generation or flavour of it you look at, is unlikely to have the same appeal as the Discover tab, FYP or Netflix/YouTube home pages.

Perhaps worrying about slop or ultra-processed content is a waste of time. There’s always been entertainment and information output that fails to make the grade. Think of all the straight-to-DVD movie releases of the 00s, or just how many videos on YouTube have single-digit views.

Whether written or visual, quality material inevitably surfaces and garners mass attention - even if, in our multi-narrative world, what gets popular can differ from person to person. Indeed, for businesses, the challenge remains the same - you need to reach the audiences you care about, which means strong creative and intelligent media placement.

If the slop takes over, I find it hard to believe people will stick around and keep watching. You only have to look at Twitter's long, slow demise or Facebook's newsfeed wasteland to see that users go where the action is. That process may take longer than you expect, and it may be hard to notice in the short term, but entropy in life is inevitable.

It’s also likely that something new will come along, some new form of entertainment that we can’t imagine yet (I remember being amazed in 2019 when TikTok started serving you videos before you signed up). Or that a format we’ve tired of (newsletters were uncool for a long time in the mid-10s) makes a comeback with a radical new look. Again, the challenge for businesses remains the same - monitor trends, examine audience behaviour, and continue to meet people where they are.

Habits take time to build, and once they’re in place, they become hard to break. That’s certainly the case with our media habits. Broadcast news remains the number one source of news in the UK, even as the landscape has fragmented and shifted over the past 15 years.

The crucial part of a habit is the reward it provides—psychologists often suggest that people change the reward instead of trying to break the habit. So, instead of trying to be healthy and not snacking during a 3pm slump, change the snack to something more nutritious.

People will always desire entertainment at particular points of their day; that entertainment ultimately boils down to individual taste - and while tastes change slowly, they do shift over time. It may feel to some people that we’re at the end of a cycle right now, but there’s always something else waiting for us around the corner.