Endlessly recycled

Nostalgia continues to thrive across both comms and culture. It could do with more remix and less remake.

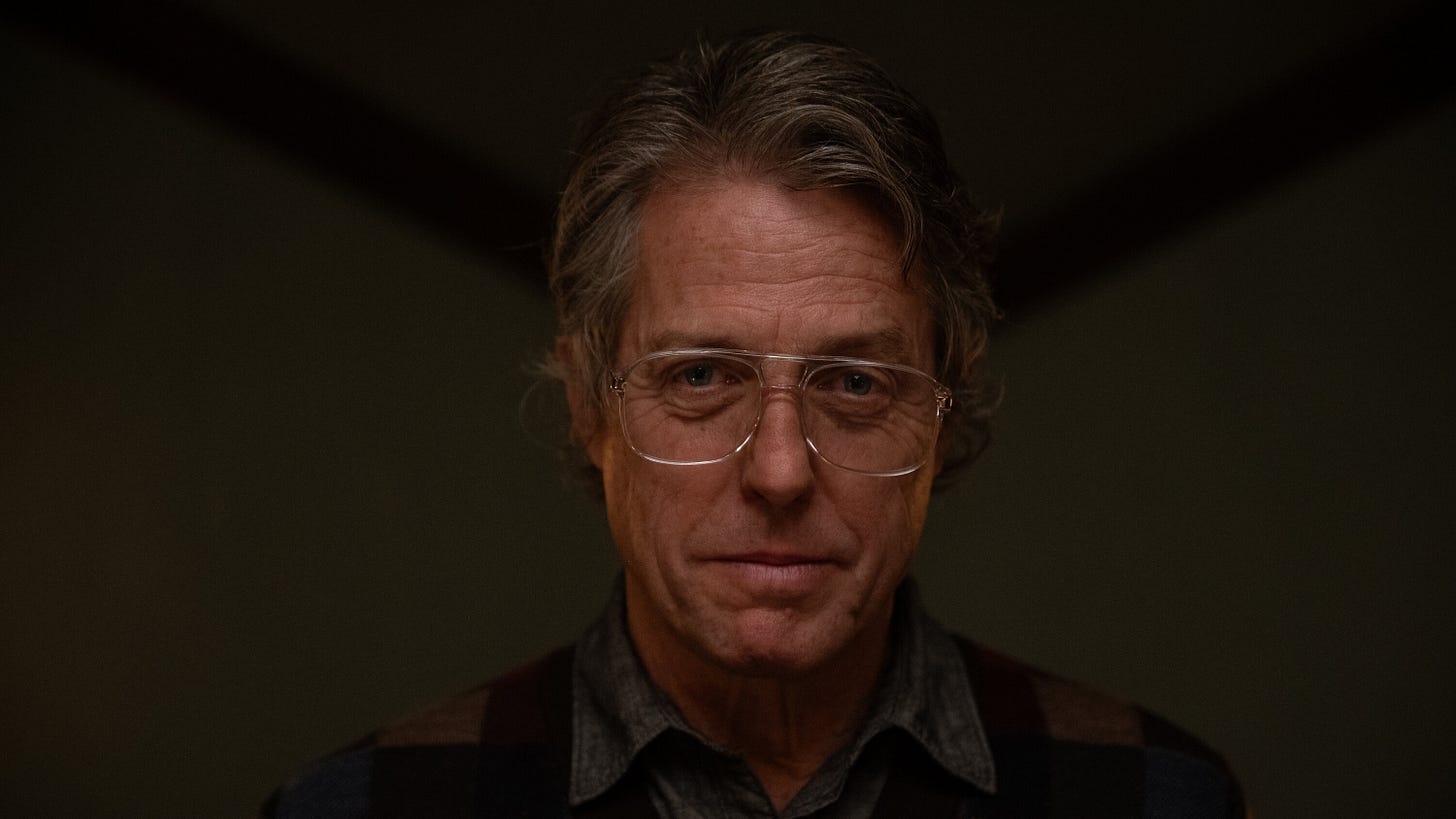

Our relationship with the past can be highly selective. I watched the A24 film Heretic at the weekend (highly creepy, would definitely recommend), and Hugh Grant’s character espouses a theory that when we recall a memory, we actually recall the last time we remembered that experience.

The theory suggests that regularly recalled memories lose their original shape, like a document that’s been photocopied too many times.

I’ve no idea whether this theory is true or whether it’s another plot device to accentuate Hugh Grant’s character, but we can see parallels in our relationship with pop culture history.

Generally, the most notable moments stick in the memory - they’re the ones that get endlessly replayed in retrospectives and timelapsed montages. For 90s montages, you inevitably see Blur vs Oasis, Blair’s first election, Euro ‘96, and Nirvana’s rise and fall. Bucket hats, adidas tracksuits, supermodels.

But the weekly snapshot offered into the 90s by BBC4’s full Top of the Pops reruns puts more of the detail of the 90s into focus. Currently, we’re in late Spring, early Summer 1997. It’s the dog days of Britpop, and the Spice Girls reign supreme.

There are a lot more big seventies collars than I remember - sported by D:Ream (Things Can Only Get Better is not a great song), Katrina and the Waves (who I was shocked to learn won Eurovision that year) and Blackstreet. There are a whole host of forgettable dance numbers, Europop and songs that were number one for a week (Gary Barlow’s first solo single is so bland it’s untrue).

This doesn’t chime with the 90s’ Sixties retro vibe that exists in my head, where it’s sideburns, Beatles haircuts and suits for days. Top of the Pops features just as many references from the 70s, with disco, and disco remixes, being particularly prevalent. This, in turn, unlocks previously forgotten memories of going to a barrage of 70s nights during my first year of University (98-99).

It shows there was just as much recycling of trends and influences in the 90s as there is right now in the 2020s. But in the 90s, this obsession with the past carried with it a sense of freedom and excitement. It contrasts distinctly with our current cultural milieu and the sense of stuckness that continues to be a narrative across the Substack-verse.

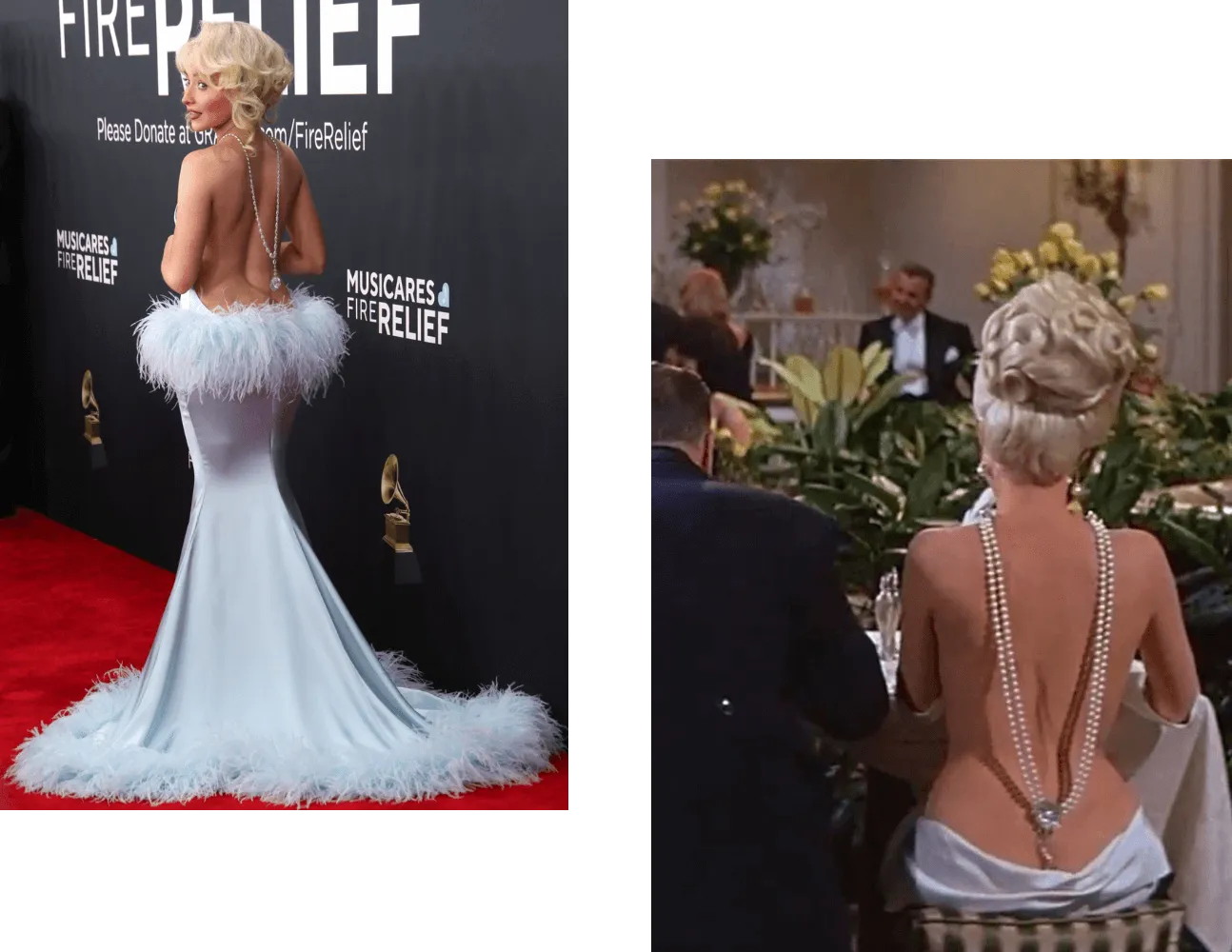

It came to light again this week in

’s excellent piece titled Reference Board Final Bosses and The Irony Epidemic. Victoria highlights how many red carpet looks, celebrity photoshoots and advertising campaigns directly reference specific looks and moments from the past.Sabrina Carpenter wears a dress that directly references Shirley MacLaine. Macauley Culkin and Brenda Song recreate a John and Yoko Rolling Stone cover. Charli XCX brings back Stella McCartney’s “About f**king time” vest top. As Vasileva says:

“Take anything you like, and chances are, it’s a reference to something everyone lost their minds about decades ago.”

Why do we feel so differently about everything being retro now, when it felt so celebrated before?

One of the most obvious explanations is our fuzzy memories, as mentioned above. It could also be the lack of online self-publishing platforms back in the 90s. Perhaps the critical consensus back then WAS that music and fashion were boring and derivative. Young people like me just didn’t care because it was all we knew. And it’s highly likely that young people today don’t care either.

Part of the reason for the continued navel-gazing around endlessly recycled culture is that the 2020s weren’t meant to be like this. One of my most re-read articles from 2018, titled The Big Flat Now, boldly predicted that our relationship with technology and social platforms would liberate us from notions of past, present and future.

Indeed, the compelling notion was that:

“It is possible that we are more creatively free today than we have ever been. The entirety of human culture has become raw material that has been open-sourced for the purposes of production.”.

This article was published in July 2018. What has changed? Why have we moved from the excitement of everything being a remix and the end of linear trends to a world where everything feels like endless rehashes and reboots, where nothing’s exciting?

We’ve packed quite a bit into the intervening seven years (God, 2018 was seven years ago), what with COVID, multiple wars, economic downturns and the rise of generative AI. We continue to underplay the ongoing rippling effects of COVID, and there’s surely some link to be investigated between the time we spent indoors, the amount of time spent during that indoor period both producing and consuming all manner of video, and where we are now.

(This piece, in fact, on Bo Burnham’s Inside, by

is excellent in that regard).Viktoria Vasileva’s view on what’s changed is the primacy of a highly reactive culture:

“Every pop culture moment, be it a red carpet, an album release, or a brand campaign, gets swallowed as a whole and spit back at us in a never-ending stream of hot takes, live reaction videos, memes, headlines, think pieces, and perhaps worst of all — LinkedIn strategy lessons.”

And this creates a problem, because you now need that cottage industry of reaction, in many creative endeavours, to generate attention and talkability. And the easiest route to generating a reaction, currently, is to reference something from the past, ideally from the 90s, tapping directly into the ready made appetite for nostalgia.

It’s a cycle which, as Vasileva argues, potentially dilutes the rise of truly original ideas.

But while I dislike that cottage industry of reaction (I particularly despise the “music teacher listens to WILDLY POPULAR SONG for the first time” genre on YouTube), I don’t know if I fully subscribe to this line of thinking.

Arguably, the more “out there” and different something is, the more likely it is to generate a strong reaction online. Of course, there’s a balance - absurdity needs to be mild to strike home, transgressions need to be acceptable. In the world of comms ideas, something like Greggs’ vegan sausage roll hits the mark perfectly.

I think the issue we face right now is too many straight remakes, and not enough remixing. We need to add some different flavours and alternative spins to our inspiration.

We’ve essentially become Be Here Now era Oasis (trying to straight up be The Beatles), when we should be more grunge (mix punk and heavy metal together to make something new).

Take as an example, the Hellman’s Super Bowl ad that reunited Meg Ryan and Billy Crystal for a When Harry Met Sally remake.

Surely there was something else they could have done to bring it into the 2020s, beyond adding an actor popular with the youth?

Even Stranger Things succumbed to this straight remake approach, having honed a reputation of three seasons for loving, well-applied pastiche.

Episode 4 of season 4 featured an almost shot-by-shot remake of the first time Clarice Starling visits Hannibal Lecter in Silence of the Lambs. You know, that bit with the line "I ate his liver with some fava beans and a nice Chianti". It felt like a cover version that sounds exactly like the original - essentially pointless if you don't add something new or give the source a new spin.

It was a far cry from other cultural touchstones known for their ability to mine references successfully. For me, Spaced is best-in class in this regard. What I loved so much about Spaced was how it mixed up its influences and used them in different contexts. One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest transposed to a restaurant in North London. A fight scene from The Matrix happening in a pub in the middle of the day.

If we lost anything from our culture in 2020, and I’m not sure we have, it would be the ability to determine the right amount of remixing to apply to existing references to make them feel new.

All ideas come from somewhere - it’s rare that anything is genuinely new. The most common form of creative thinking is to take two entirely unrelated ideas and fuse them to make something great.

This approach also works particularly well if you’re trying to sell an idea to a client or internal stakeholder. "What if we took the well-understood motifs from prngraphy and applied them to social distancing" . Ikea applying the language of casual dating to shopping for a mattress. Jaws in space.

Great communications ideas and concepts need that breadth - brand campaigns are rarely in the business of straight remakes. The best work mixes up its influences from various sources - that mix can't be totally random, or the end product will lack harmony.

And you need just the right amount of inputs, or else you'll create the dreaded Frankenstein's monster of too many ideas mashed together in one place. It's a process of alchemy, and as with many examples we see today, it might be a process you don't always get 100% right. But you'll know it when you see it because the best blends, the most compelling combinations, feel right. They make sense for everyone who sees them, conjuring fuzzy recollections of shared experiences.