Change it back

It's been five years since COVID-19 entered our lives. Everything appears to be back to "normal". But is that really the case?

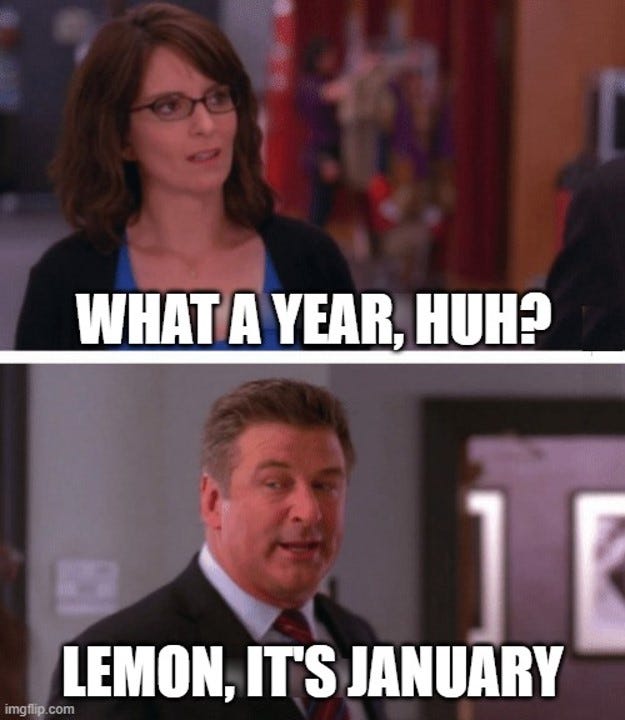

January is very nearly over. We’ve packed a lot into this year’s edition, particularly in the Western world. We’re arguably at “Lemon, it’s January” activity levels.

And while a lot has changed, in my view we’re not quite into “unprecedented” step-change territory.

It arguably feels like the latest season in a long-running prestige HBO drama.

Call it simply “The Pandemic”.

Many of the narratives we see flying around our newsfeeds and FYPs arguably represent direct reverberations from the changes forced on us by COVID-19.

You can see it in the continued search for economic growth and the struggles to curb inflationary pressures on both sides of the Atlantic.

You can see it in the continued cost of living crisis affecting vast swathes of people in the UK.

In the outsized ambitions and outlandish proclamations of big tech’s various big bosses. All those companies experienced outsized growth during the pandemic, and all are either trying to protect those positions or desperately embracing “AI” to reattain that growth.

You could also subscribe to the argument tabled by Garbage Day’s Ryan Broderick that Silicon Valley's men (it’s always the men) had their minds warped by those fever dream pandemic days. And that much of their…erratic behaviour stems directly from the effects of watching the world get turned upside down in a matter of weeks.

But the thing is, it doesn’t feel like we mention the pandemic all that much. I’m sure there’ll be some retrospective pieces when we reach the fifth anniversary of UK lockdown one. Otherwise, the whole thing feels like a collective fever dream the world experienced simultaneously.

The pandemic may be officially “over”, but we're still living through it. Still part of that long-running psycho drama “The Pandemic” (capital p). And we can feel its effects playing out, both emotionally and practically.

In this piece on video game 1000XRESIST (thanks to James Whatley for the link), Emily Price captures some of those emotional effects. Some of the feelings that swirled around during the early stages and lockdowns - feeling “powerless, anxious, disconnected. Like the world was ending, maybe?”

The video game analogy works remarkably well, given how unreal the whole situation felt - that almost dream-like sense of time standing still, while it also simultaneously flowed past in a headlong rush.

Price suggests that the dream-like nature of the pandemic, its inherent surreality, has been emphasised by an absence of COVID from media and culture. As she puts it:

“What’s on TV, in novels and certainly in games has no representation of the epidemic that has changed all our lives so much.”

But why is it that we don’t see more representations of this global collective experience on our screens? One argument is that no one wants to hear about COVID. We spent nearly two years with it at the top of the news agenda, and we know that many people continue to turn away from the news because it is so unrelentingly bleak. It would take a brave commissioning editor to turn against this trend.

Emily Price also argues we don’t mention it because mentioning the pandemic would force us to acknowledge that our notion that it’s “all over” is demonstrably false. We continue to live through mass viral outbreaks that put strains on our infrastructure - just look at this FT graphical representation of the number of people hospitalised by this year’s flu:

Perhaps another reason we’ve buried some of the emotional impacts of the pandemic is that we can no longer see much of the intense practical change we experienced during 2020-21.

This reversion to the past is not what we anticipate. But then we often fail to acknowledge our innate human capacity to overpredict short-term change and underappreciate long-term change.

Indeed, during the pandemic, you couldn’t move for articles and hot takes about how the post-pandemic world would be unrecognisable from what came before.

Major metropolitan office districts would be wastelands. Physical conferences and networking events were a waste of time and money and would definitely be replaced by online-only meetups.

Companies would be free to hire more broadly, an army of the best workers taking up remote roles. Commuting would be a breeze, as people worked more flexibly and rush hour became a thing of the past.

While the pandemic showed humans’ capacity for change, as well as our innate ability to survive, the post-pandemic era also indicates just how habitual we are. And the habits appear to be winning out over the changes. But it’s not been a frictionless return to pre-pandemic habits in all aspects of our lives.

You can feel that friction most acutely in the ongoing debates around hybrid working. You might be as sick of hearing about hybrid working as many people were of hearing about COVID-19. But it’s the debate that refuses to go away. A debate given a fresh lease of life by both WPP’s recent “four days in the office” announcement and (checks notes) a couple of old white men claiming WFH is a sin.

As someone who commutes into the office around 70% of the time, I can see both sides of the debate. But I’m also painfully aware that I am in a privileged position where my wife and I can make childcare commitments work around our careers without too much impact on either.

Looking beyond the tedious old white man headlines and the endless LinkedIn debate exists a genuine problem that’s not yet been truly solved (in my opinion). That is the enduring terrible quality of hybrid meetings.

I have yet to experience a meeting where a bunch of people in a room and a bunch of people online have a seamless, equitable experience. Meetings work well when everyone is remote or when everyone is physical. The in-between is terrible.

And while, of course, you can (and I do a lot) dial-in from your desk, going into the office to spend all day on calls defeats the object of being in the office. I’d much rather stay at home in that situation - for one thing, I don’t have to share my Wi-Fi with 180 other people.

The flexibility and freedom enforced home working offered many people during the pandemic is arguably one of the only factors we haven’t forgotten from that strange, surreal time. We might romanticise it slightly, and forget that some people struggled to create effective boundaries between work and home when it all happened in the same room. However, remote and hybrid working remain at the top of the wishlist for many desk-based knowledge workers.

Returning to our HBO prestige drama, The Pandemic, we see both noticeable and less-noticeable effects of COVID running through many of the narratives that make up our modern world. But what can PR and comms people take from being more aware of the pandemic’s effect on society?

Well, firstly, from an operational POV, there’s clearly a need to take a position on hybrid and remote working. Leaders must escape the LinkedIn posturing and use evidence to ascertain which approach delivers the best results. And that’s results both in terms of outputs and in terms of talent attraction and retention. Base your decisions on data, and don’t be swayed by some old white man who wants everyone in the office so he has some company in between his long breakfasts and lunches.

Secondly, it’s always worth remembering one of my favourite quotes, from Bill Gates (and paraphrased many times throughout the 20th Century):

“People often overestimate what will happen in the next two years and underestimate what will happen in ten.”

Our habits as human beings are remarkably sticky - it’s perhaps unsurprising that so many aspects of pre-pandemic life have returned now that we’re getting further and further away from the UK’s lockdowns. We should apply this long-term lens to more stories and news cycles. Sure, the Meta fact-checking announcement is big news - but will it genuinely change the way the majority of people use Facebook and Instagram?

In a world where the speed of the news cycle seems to increase exponentially every year, there’s never any harm in carving out time to look at the bigger picture.

Stepping back and attempting to see how all the pieces fit together, to understand how we got here and what we can learn from the journey. Because while it feels like we’ve packed a significant amount into the year so far, you might also argue that this is simply an explosive finale to the latest season of modern life.