Swimming outside the mainstream

As popular culture becomes ever more fragmented, we need to get smarter when selecting our shared reference points

One person asked me over the summer (Hi Joe Hughes) whether I'd be writing anything about Barbenheimer. I considered it, but felt I didn't have enough of an angle to justify a 1,000-word-ish piece. I based my take on the fact that, even in our world where we have completely democratised the creation and discovery of entertainment, our social feeds were full of memes based on two movies fitting an age-old model - the Hollywood summer blockbuster. There's something about the shared experience, the small talk opener "Have you seen x show or movie?" that continues to thrive, even as our feeds and media diets become more and more algorithmically individualised.

As anyone who's read even one pop psychology book knows, humans are innately social creatures. At a primal level, we crave the safety of the herd. Discussing what's popular is our modern way of feeling connected to the tribe. I specifically watched Bird Box and Squid Game to understand all the memes shared online and be part of the broader conversation. Switched the other way round, I've referenced one of my favourite shows, HBO's Barry, loads of times - no one else in my social circle has seen it. That didn't dampen my enthusiasm for the show or make me stop watching it; I replaced this IRL chatter with plenty of blogs on Barry, but it's a poor facsimile. (Incidentally, if you're a Barry fan, reply or comment to let me know).

The feeling of connection, of shared collective consciousness, is another reason why Twitter continues to rumble on - despite people leaving in droves and the plethora of alternatives, Twitter still provides a central drama that generates conversation. Generally, this comes from its main character, its drama of the day - one tweet or thread sparking a bunch of replies, giving those still using the platform something to talk about. TikTok and Instagram may now be the pre-eminent platforms in the West, but they are highly individualised experiences. The main characters and the drama on those platforms happen in microcosms - and, particularly for those people who become main characters, this is arguably a good thing.

Mainstream main character energy, juxtaposed with a long tail of sub-cultures and niche interests, represents much of our current entertainment experience in 2023. Some mega-hits become subsumed into the "collective consciousness", generating highly recognisable memes. And then there's everything else - still popular, but not in the "small talk with a colleague" realm of Barbenheimer. And, in many ways, this is a state that's worth celebrating. Our every taste catered for, but without so much fragmentation that we feel isolated by our cultural touchpoints.

But the fact that much of what we consume is either super-popular or appealing to a small but dedicated crowd appears to be putting a strain on those creating the shows/movies/videos we love to consume.

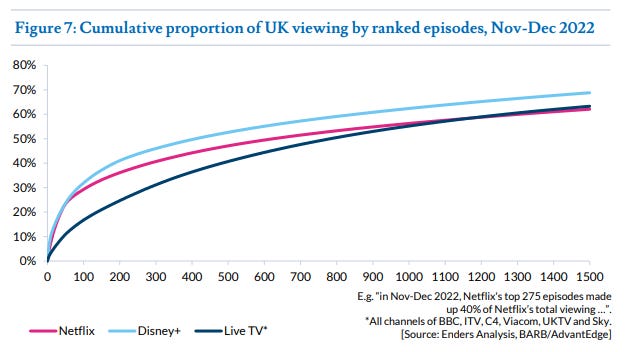

Statistically, people watch a smaller pool of shows via their streaming services than they do via traditional broadcast, linear TV. The top 250 episodes on Netflix account for 39% of the service's total viewing. By comparison, the top 250 episodes on linear TV account for 28% of its viewing.

Filmmaker DB highlights this same choice paradox in his long read, The Real Cost of Good Movies (And How To Pay For It) (via

). He browsed his Netflix and calculated that the algorithm recommended around 500 titles. That's only approximately 10% of the 4,165 titles that US Netflix has available to watch. Of the sVoD platforms I use, only Disney+ has a "browse all" function. You either need to know what you want to watch (a time-consuming task in and of itself if you want to watch Spinal Tap but aren't sure what streaming service it's on), or you bow to the wisdom of the algorithm.Streaming services promise unrivalled choice, but it feels like there's less choice than your local Blockbuster back in the day. And even if there is choice, most people aren't taking advantage of those options - browsing for a while before watching Schitt's Creek (or similar) again. And the way the economics of streaming work, only those movies or TV shows that sit within the top 250 episodes seem likely to generate any revenue. That's a key argument of the piece: the economics of how anyone involved in making movies/TV shows gets paid being unsustainable for all but the most prominent franchises. Add the increased adoption of generative AI in production, and you get an insight into why the Hollywood strike action shows no sign of abating.

But for consumers, is there anything wrong with an essentially two-tier movie/TV show landscape? It's not so dissimilar to YouTube or Twitch, with the biggest stars drawing the most significant revenue and others focusing on their most loyal fans via merchandise and Patreon sponsorship.

However, the mainstream entertainment industry only needs to look at our hollowed-out news media landscape for a cautionary tale of what can happen when there is only the binary option of the biggest or smallest outlets. A small pool of options quickly feels like too little choice, with brutal competition fueling the consolidation of platforms. Only the most significant, established institutions stick around in the media. For the Marvel Cinematic Universe and Lord of the Rings, think the New York Times and the Daily Mail.

Eventually, too little choice becomes as bad an option as too much choice, and viewers gradually drift away. As the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism found in their latest digital news report, more and more people are actively switching off the news. I'd be a fool to suggest people will switch off their TVs en masse, but you could easily choose to ignore the new offerings from the primary streaming services. The Enders Analysis report on Netflix's total viewing didn't mention which were the 250 episodes that dominated people's viewing. I'd wager the likes of Friends, The Office, and Schitt's Creek featured heavily, however.

This two-tier entertainment system is likely also bad news for those of us fond of introducing popular cultural zeitgeists into our campaign plans and creative ideas. The mainstream macro pool to choose from will likely contract over the next few years. Even if the economics around royalties get sorted out, there will be a lag thanks to the strike action. The good news, as many people have found over the past few years, is that there is plenty of success from mining those less mainstream trends and interest groups.

But it's invariably a more complicated and time-consuming route to take. Doing a Barbenheimer meme over the summer was obvious, given the ubiquity of the trend. Going deeper and more specific takes time. It requires a more nuanced understanding of your audience(s) and how they spend their attention. It will likely take you on to platforms you might not use every day - you'll probably need an audience safari (to coin a Pixar phrase) to get a sense of what's happening in their worlds. Taking a more interest-based, less mainstream approach to your planning is also a trickier sell for clients. Plenty of CEOs still prize print coverage and love to see their face in the weekend edition of the FT. They're not always convinced about the value of doing a podcast or sponsoring an influential Substack. It makes demonstrating the impact and effectiveness of a multichannel, interest-led campaign even more important.

And, of course, it's not a zero-sum game - just because a comms campaign is multichannel doesn't mean it will completely ignore the mainstream, popular platforms and the macro trends. You still need scale to change hearts and minds. But if the mainstream continues to contract, and all our ideas start there, all our campaigns will look exactly the same. And as much as I loved the juxtaposition of the Barbenheimer memes, there are only so many you need in your LinkedIn feed before it all gets a bit repetitive. Give me some Barry-style ideas to offset the Barbenheimer any day of the week.