This summer, I passed 15 years of advising and supporting clients with their social media, digital communications, and marketing. I started at immediate future in the summer of 2008, moving into "proper grown-up" agency world after six years in the music "business". I spent that first summer doing what we now call influencer outreach to creators on MySpace. We didn't have that terminology to describe them back then; we called the group we identified "slash/slashers", so named because they self-described as DJ/designer/writer in their MySpace profiles.

With Myspace long gone, every passing year and subtle shift in the online landscape makes me wonder how long I can keep doing it. The ad industry, in particular, is obsessed with youth and has a real issue with people ageing out of agencies.

Luckily, I work in strategic communications (we'll leave the question of what unstrategic communications are for another day), where there are arguably too many older white men rather than not enough. I also have clients that target younger audiences to keep me in touch at one end of the spectrum, with an increasing focus on LinkedIn at the other, which helps me stay relevant. However, I'm not a TikTok native like I was a Twitter and Tumblr native back in the day. When I spend time immersed in the worlds of younger people, it's not quite a foreign country, particularly given how nineties all the fashion is. But it’s not far off.

And while the world younger people live in isn't quite a foreign country for me now, it's certainly the direction of travel for the population as a whole. Among the headlines around how much more liberal-minded the UK is, the British Social Attitudes research also highlights how age is now the dominant political divide in the UK. You may expect that to follow the received wisdom that people get more conservative as they get older - every new generation's values are at odds with their parents.

But according to the BSA data, there's actually minimal divergence on left-right views - and this data backs up other research showing how a variety of factors shape people's opinions, not just age. As the UK is generally more liberal, so this liberal thinking applies to all age groups.

A more compelling argument for the distinct age-based schism between Labour and Conservative voters is an economic one. As

puts it in his excellent piece, Liz Truss was right (don't worry, it's not a pro-Liz article): there's a "growing belief amongst younger people that they can't succeed just by working hard, a view the government have reinforced."As evidenced by Rishi Sunak's recent u-turn on net zero, the perception is that the Tories don't care about young people - in an ageing population, the government protects pensions, house prices and the establishment. More and more people in their 20s and 30s have entirely given up on the idea of owning a house, an issue exacerbated by persistent failures to hit house-building targets. Taxes, particularly tax rises, "benefit older people in need of pensions and healthcare". Brexit may have faded from view as a hot-button political topic, but its ramifications still reverberate around the economy. One prominent example - it's becoming financially unviable for bands to tour, and the gigs that do take place are astronomically expensive (have you seen the price of Glastonbury tickets next year?). The economy lurches from crisis to crisis, struggling for growth thanks to Brexit effects amplified by war and the pandemic. Younger people didn't vote for Brexit, but they'll be left mopping up the mess for a long time.

The baby boomer vs Gen Z political divide doesn’t stem from ideology - it stems from primarily economic factors, leading to that feeling that of being a generation cut adrift in favour of protecting our ageing population.

As ever when reviewing such broad demographics, these are relatively crude generalisations - the cohort of younger people identified in the BSA research covers 18-34 year-olds, a 16-year gap encompassing both Gen Z and millennials. But there’s truth in the findings. We know from recent elections that the traditional indicators for predicting and explaining how different groups vote have crumbled away. For the past 30-40 years, the newspaper you read was the most significant indicator of how you would vote. In the 2020s, maybe we should replace newspapers with TV services.

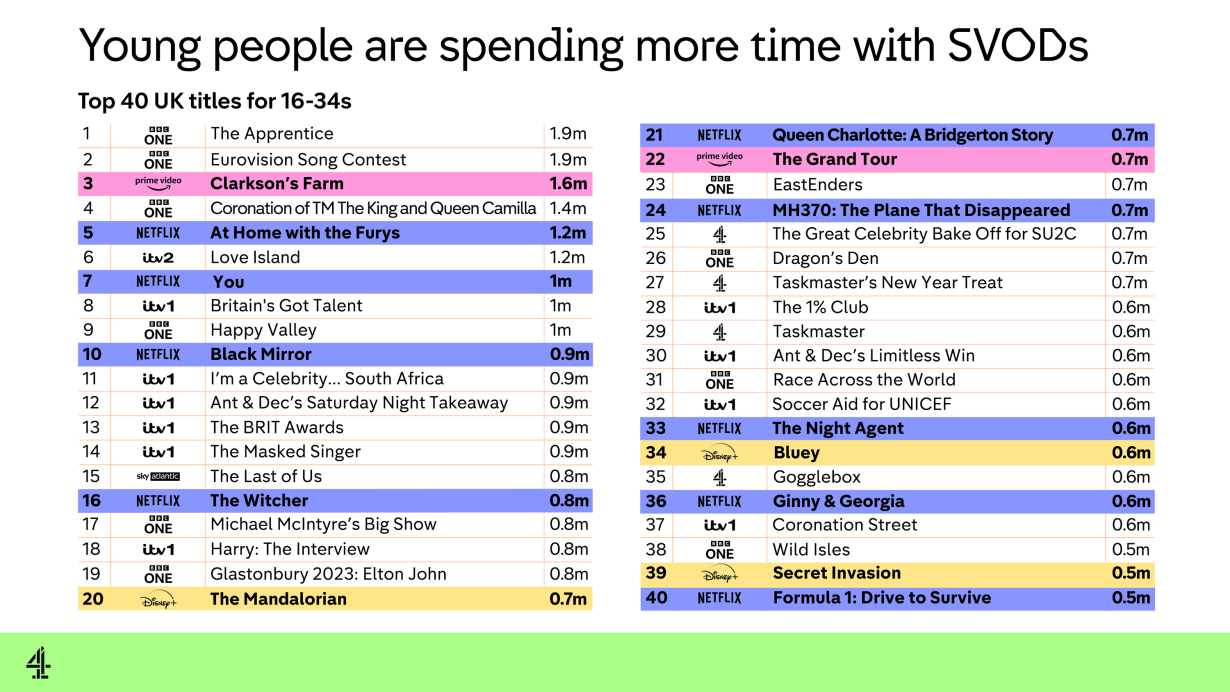

Channel 4 CEO Alex Mahon's excellent RTS Cambridge speech included some fascinating data points on TV consumption. The first chart below displays the most popular TV shows from the past 12 months (data sourced from BARB):

What's most striking about this chart, as Alex points out in her speech, is that there's only one sVOD show in the top 40, and that features a presenter who honed his skills on the BBC. What also stuck out for me, alongside the things you'd expect to see like the two Coronations (the King and the Street), were just how many big setpiece BBC/ITV drama shows you see. Very few of these shows generate the kind of memes and online chatter that the likes of Succession or The Mandalorian do, but millions of people watch them. But, as the following chart shows, the lack of "setpiece drama memes" is arguably explained perfectly by who watches those dramas. This one takes the same data but displays the most popular TV shows among 16-34s (younger people, as per the BSA study):

There's overlap, but there are significantly fewer PSB setpiece dramas and many more streaming service shows (and even a Sky Atlantic show, The Last of Us). The schism in age-based viewing choices and habits is striking - a division that further highlights that the age gap is the single most significant divide of the modern era.

FWIW, I did try to find historical data to show that has always been the case - but the publicly available BARB stats don't include demographic breakdown. I'm sure that it IS the case that younger people have always had different tastes from their parents. Still, I think the additional political and economic factors amplify these differences to make it feel like different generations live in different worlds.

Both the BSA research and Channel 4's presentation of BARB data speak to a need, in our tumultuous times, for always starting our comms and campaigning work with audiences and audience understanding at the top of the agenda. We can't assume that we know everything about everyone; we can't assume that everyone is just like us (they're really not). Plenty of what people who work in advermarketingPR consider highly prevalent habits (watching Netflix, listening to podcasts) are not habitual outside of our bubble. We can't assume that old battle lines and received wisdom still hold. We're still living through the long-term effects of the seismic moments we've experienced over the past ten years (Brexit, the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, the coalition's drive for "austerity"). These moments continue to shape and shift people's attitudes, beliefs and ways of living.

The key to success when planning campaigns is staying malleable and accepting that there's always something to learn, something new to discover. We can't become calcified in our views and assume that the received wisdom always applies. We need to force our brains outside of their natural comfort zone of "what you see is all there is" (to quote the inimitable Daniel Kahneman) - otherwise, we risk alienating key audience groups in the same way that the Conservatives continue to alienate the younger end of the voting cohort. If we want to stay relevant, no matter the age or socio-economic profile or location or sector of our audiences, we need to start with understanding. Otherwise, our campaigns risk being more Myspace than YouTube - unable to keep up with the times.