Unlocking potential over productivity

Goldman Sachs says generative AI will boost productivity. But focusing on AI ignores deeper divisions around work in the UK.

Many of our concepts and ideas around work still stem from 19th-century industrial revolution practices. Many people have shifted away from the Victorian 9-to-5 with the accompanying commute, but other concepts, like the hour-long lunch break, linger on. Another concept that clings to its Victorian definition is productivity.

Measuring productivity when you're making something is easy; I run a bakery, so I need to make baked goods to sell. I work out how many baked goods I can physically make and look to optimise my processes to get as many pain au chocolat out of the kitchen as I can (as an aside, running a bakery would be an ideal alternative career for me).

Measuring the productivity of knowledge workers is more complex. Consider your job; if you're like me, a day of meetings may feel less productive. "I haven't done any actual work", you say. But if those meetings delivered five critical decisions that moved projects and campaigns forwards, that's pretty productive, despite how the experience may feel.

Some people equate productivity with the volume of emails they send; looking busy = maximum productivity. You might also think about the number of documents you produce. But sometimes, spending a whole day unlocking a creative platform that will only be one slide in a deck is the most valuable and, therefore, productive thing you can do.

The official definition of cognitive productivity used by statisticians values "the output of cognitive activity simply by assuming it is proportional to the quantity of labor input being used to produce it." In other words, you spent time doing something, and in the act of spending time, you were productive.

Anyone who works in any knowledge job, not just comms and marketing, knows this is untrue. Filling your days with meaningless menial tasks may feel productive in the outputs it creates but can lack tangible outcomes and value.

The difficulties in measuring cognitive activity may explain why productivity has been relatively static for the past 20 years. Moving from analogue offices to PC and then internet-based work in the 90s and early 00s saw increased productivity - applications like Excel and PowerPoint enabled us to do more stuff - but it has remained relatively static since then.

It is a conundrum that comes up continually in the media - why aren't we more productive? How can we buck this long-term inertia?

In unsurprising news, some analysts believe that generative AI is the answer. We've seen several frothy headlines doing the rounds, based on reports from the likes of Goldman Sachs and the Brookings Institution predicting that tools like ChatGPT could help boost productivity in the US by 1.5% (which would be significant, given it remains under 1% at the moment).

Tools like ChatGPT overlay with the model for measuring productivity relatively neatly. Automating the creation of outputs gives you more time to make more of those outputs, more stuff. Ergo, based on the definition, you are more productive.

When seeing these kinds of frothy headlines in the media, I worry that ministers, MPs and advisors (the "key decision makers" in the UK) see an easy solution to the productivity gap. According to Ben Evans, US firm Palantir is seeing increased demand for generative AI software from traditional laggards like governments and defence departments. Given the increasingly short-term thinking applied by governments, particularly in the UK, quick and simplistic fixes like making software available can be extremely attractive.

This simplistic approach to productivity ignores broader, more complex issues that restrict growth and development in the UK.

One such issue is the poor transport links outside of London. According to research by the Centre for Cities, published last year, only 40% of the population of British cities can reach their city's centre in 30 minutes, compared to 67% in mainland Europe. And researchers equate the ease with which people can access cities with their productivity. The thinking is that more people in a city centre means better access to talent and skills and the creation of "natural clusters of creativity".

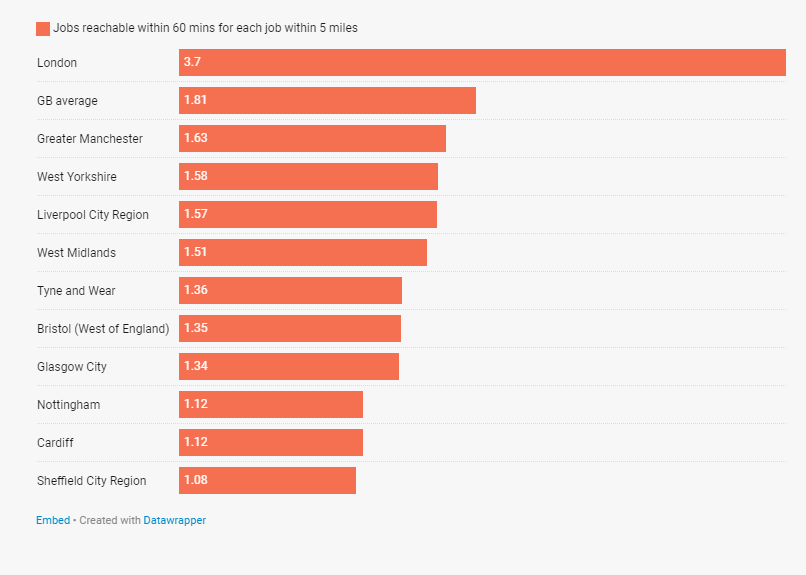

We can back this up with research from 2021 that showed the number of jobs reachable within 60 minutes on public transport was more than double in London than the UK average.

But that research also showed the complexity involved in "levelling up" places outside of London. Although improving public transport links will make a big difference to the options available for people living in big cities around the UK, it isn't a panacea to driving more substantial regional growth. UK Onward highlight the disparities in qualification levels and the mix of job options available as significant factors in improving income and productivity.

And let's be under no illusions here - we live in a starkly divided society regarding how much we get paid and how we work.

One of my favourite pieces of data visualisation of late, sourced from the excellent Quantum of Solazzo newsletter, highlights how the ability to work from home, so valuable to many of us in our world of comms and PR, is generally only available to people with higher incomes.

And to compound that disparity and divide, 74% of "high income, low travel" local authorities are based in and around London.

One of the biggest things we heard at Teneo when we surveyed colleagues about working for us during the pandemic was how much more productive they felt working from home. The evidence supporting that feeling is sparse - this study says it's hard to tell either way. But there are undoubtedly benefits to working from home. And access to those benefits is a privilege, and it is a privilege that is overwhelmingly enjoyed only by well-off people living in and around London.

(As an aside, I looked into employees' legal rights around flexible working and WFH. The Government does offer the opportunity for anyone to apply for flexible working (which includes working from home). Still, you must have completed 26 weeks service, and the decision can take up to three months (!)).

I've spent a few days at Advertising Week Europe this week, and it won't surprise you to hear that ChatGPT and generative AI was a hot topic (having AI in the title of your panel guaranteed you an audience). Panels were full of sweeping statements about how AI would fundamentally change AI and improve everything for everyone.

We need to be sceptical of such narratives, just as we need to be sceptical about extensive research reports that claim generative AI tools will magically increase productivity. As human beings, we love stories, and we love simple stories we can easily retell.

The challenge is that there are rarely simple solutions to complex problems. At Teneo, we specialise in expressing complex concepts in simple terms. But we can't make the solutions simple. That would be over-simplistic.

Solutions take time. They take consistency. They take collaboration. They require everyone involved to be pulling in the same direction. And they are hard work. But they are worth it because they're always more effective in the long run.

Don't fall into the trap of thinking new technology, as exciting as something like generative AI is, can provide all the answers with a simple one-stop solution.

Quick fixes may work in the short term, but in the long term, they're counter-productive. They can even make everything worse, requiring even more time and energy to fix.

We can’t rely on technology to fix everything for us; we need to find clever ways to apply technology so that it reduces our geographical disparities. I worry that the blanket application of ChatGPT to “solve” productivity will only widen those disparities further. We need better work options for everyone in this country, and there’s no quick fix for that, no matter how much we’d love one.