Twitter's outsized influence on media

New data reveals just how much of a mutual echo chamber Twitter and mainstream media outlets create.

Some Twitter-based statistics to kick off this week’s newsletter:

Only 9% of social media users chose Twitter as one of their main social media sites.

A 55% increase in the number of tweets on a topic before it is covered in media leads to an increase in news articles on said topic, corresponding to 17% of the mean.

In other words, a minority of Twitter users have an outsized effect on the mainstream news agenda.

Twitter driving media coverage is something I'd always suspected took place, but I'd never seen any compelling research into how significant that effect is.

Academics in France conducted new research from which the final statistic on how often Twitter activity drives media coverage comes. Their data set covers August 2018 - July 2019, with an updated version of the study published at the end of June this year. The methodology behind the analysis of around 1.8 billion tweets is pretty dense, using a proprietary ranking system of influence and "news pressure" to try and show the direct impact Twitter has on editorial decisions.

I assumed the most significant factor driving Twitter’s influence on the media was the outsized impact journalists and other media members have on Twitter discourse generally.

Journalists, alongside celebrities and politicians, are Twitter's most prominent power users. Journalists tend to follow each other and overwhelmingly use Twitter to announce "breaking" news stories while they wait for their outlet to publish their full articles. Internet culture is all about being first; for journalists, being the first to break a story comes with a significant dose of clout.

The researchers also anticipated this factor - according to their analysis, removing journalists’ Twitter profiles makes little difference to the trends seen in the data.

The popularity of a story on Twitter is now a crucial indicator of whether media outlets cover it in their publications.

This study does have a distinct 'French' angle - as you would expect of a study covering French tweets and media articles. Some of the stories that first blew up on Twitter were in English - and in theory, already covered by mainstream media, as opposed to purely 'Twitter stories'. However, there were many examples of stories that did truly originate on Twitter, either hashtag-based occurrences or footage of real-world events shared widely on the platform.

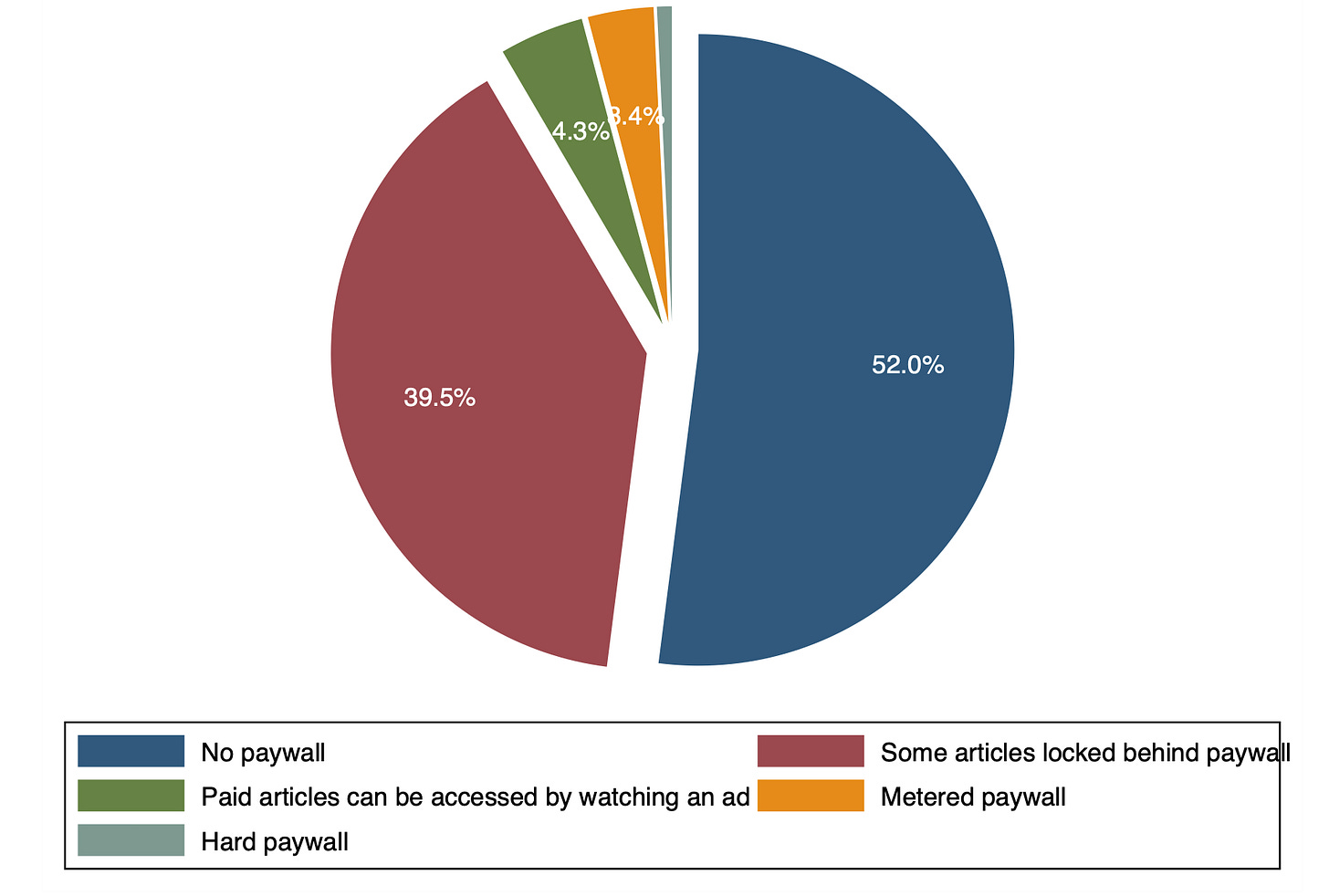

Another factor at play stems from an existing schism in online media. Namely the different revenue generation models used by media outlets.

Publications that rely on click-based advertising or use soft-based paywalls (i.e. “watch an ad to access this article”) are statistically more likely to cover news stories that trend on Twitter first. The logic here is rudimentary - if people are already tweeting about a story, they're more likely to click on an article and see/click on an ad within it. For many of these publishers, article generation is a volume game - throw a whole bunch of stories at the metaphorical wall and see what sticks clicks. With its trending topics and high index of news-based tweets, Twitter is the ideal platform for this kind of news spotting.

Sites that use different revenue models, particularly a hard paywall, rely less on Twitter to inform their editorial decisions (and generally post fewer articles). Some, like the New York Times and The Guardian, explicitly advise their staff and writers against using Twitter as a proxy for public opinion or popularity.

And yet Twitter's outsize influence rumbles along with minimal third-party scrutiny.

One of the many reasons media and politicians want to rein in big tech is the aforementioned outsize influence. However, the outsize impact of Twitter is the elephant in the room when it comes to social media regulation. All the focus tends to be on Meta's platforms, TikTok (because it's Chinese) and YouTube; the pernicious effects of Twitter tend to fly under the radar. If any other company had admitted to keeping President Trump's account live because it was good for its clout, the media would have vilified it. Twitter escaped such vilification. But given journalists and politicians are two of the heaviest users of the platform, it's no surprise that its outsized influence goes relatively unremarked upon.

Even with all of the uncertainty caused by Elon Musk's "will he/won't he" takeover, Twitter's role in inspiring media coverage is unlikely to change soon. And that presents a significant challenge for brands and businesses. Twitter is at the core of all social media monitoring services - it's where we tend to look first if we're tracking an issue. That's partly due to the aforementioned heavy use by media and partly because it's one of the only platforms (alongside Reddit) to provide open API access. And we know, both from firsthand experience and this new research, that something blowing up on Twitter can quickly become a mainstream news story.

And in our world of comms, media coverage of an issue is...well, an issue. But the challenge is gauging how much of an issue it is. Suppose the media source the story from Twitter, which represents a tiny sliver of public opinion, and then publish that same story because of its Twitter traction. Is that cumulative traction genuine?

Generally, if a story has media coverage, it needs, at the very least, a response and probably some action. But the worry with responding to an article sourced from Twitter is that businesses give a story more credence by responding or taking action. I wrote a story a few years ago about the 'backlash' to a Calvin Klein advert. Only 3% of posts on the topic criticised the ad; the majority referred to coverage of the criticism and Calvin Klein pulling the campaign. Taking action is often the factor that turns a story truly mainstream; initial media coverage is generally the beginning - and the end if companies choose to ride it out.

So how do businesses decide what is just "Twitter talk" and what has the potential to cause significant reputational damage? Two ways we're helping clients with these tricky decisions. Firstly, by using historical precedent. Our Risk Impact Index pulls on various data sources, including share prices, media and Twitter, to map similar previous issues and crises. By overlaying different data points, we can more accurately model if a future incident is an existential threat or just a bump in the road.

The other tactic we've used isn't particularly revolutionary - we went out and talked to people. We ran a set of focus groups that aimed to understand whether or not a representative group of our target audience was aware of an issue on Twitter. Some speedy turnaround first-party research can be invaluable in informing decision-making around how you respond to a topic. Sometimes speed is of the essence, but for something set to rumble on, how real people think and feel is crucial.

In many ways, Twitter is a necessary evil. It has its uses, but on most days - days when the Prime Minister isn’t refusing to resign or the Lioness aren’t winning England’s first major international football trophy in over half a century - Twitter is supremely insular. If you’re in the game, you know what’s going on. Otherwise, you might look in and steer clear. The challenge for media outlets is that if they continue to source stories from Twitter, they risk turning even more people off news than ever before.

For everyone else, we need to evaluate any Twitter-based news or trend with a well-trained critical eye.