The transparency issue

Reviewing the big tech transparency reports submitted as part of the EU's new Digital Services Act.

I based my original idea for starting a newsletter around the central tenet "I read, so you don't have to". And while this tenet doesn't apply to all my posts, I generally base my thoughts on some of the things I've read over the past week. And sometimes, I worry that you've all read what I'm writing about, making my email easy to skip and delete.

But I'd be surprised if many of you have read the DSA (Digital Services Act) Transparency Reports that big tech platforms operating in the EU are now required to submit every six months. I have the benefit of being on gardening leave, so I pulled myself away from my guitar and flicked through a selection of submissions.

TikTok and LinkedIn used their reports to hammer home key messages about who they are and what they do. Their business narratives shone through, even in a functional, technical document. Meta submitted separately for Facebook and Instagram and was very Meta in its approach - robotic, by the numbers, not much humanity. Twitter's read like a long rant, reeking of "we're only doing this cos we have to"-surly teenager vibes. Google's was the most obtuse and difficult to understand; less surly teenager and more "expensive lawyers told us to respond in this way".

The obligation to provide various data was consistent across the reports I read (and I confess I've not read them all) - data on moderation and content removal in particular. I've not seen anyone bring the data shared into one place, so I put together a rudimentary Excel to compare some of the numbers on offer.

(Weirdly, the DSA doesn't stipulate timeframes for the data provided, so Google submitted two weeks' worth of numbers; Meta offered five months. I've used one-month figures; where these weren't available, I used numbers presented as an average to create a one-month composite.)

The numbers provide some interesting nuggets of information:

LinkedIn only removes a tiny number of posts, given its size and scale. Perhaps, as a professional network with limited search functionality, it's not a scam/spam hotbed. Or the posts are out there and aren't being spotted. I've reported one ongoing crypto/impersonation scam multiple times.

Twitter only removed 50k posts but shut down 2 million accounts, a perfect snapshot of the current leadership's approach to content moderation on the platform.

The content removal and account suspension numbers across the most prominent platforms, particularly the Meta-owned ones, are hard to comprehend. The best part of 25 million posts and 22 million accounts were removed across Facebook and Instagram in one month, in the EU alone. The vast majority of these removals are automated and likely happen exceptionally quickly in the ongoing race between scammer/spammer software and that used by big tech.

As fascinating as those numbers are, reading through the six transparency reports I looked at, I couldn't help but feel there wasn't much transparency on show. There were a lot of numbers, a lot of box-ticking, and some valuable intel for big tech platforms running the same exercise I've just done to compare and contrast their approaches. But there’s nothing much new on show: these are still huge companies dealing with vast numbers of users and posts, applying very similar processes to try and keep unsavoury content off their platforms.

What’s missing from this process is context. These transparency reports are like the worst campaign summaries you've ever seen. "We hit 2 million impressions!". Great - so what?

TikTok removed 4 million videos from its platform. The largest buckets for those 4 million videos were "sensitive and mature themes" and "regulated goods and commercial activities". This doesn’t tell us much beyond the fact that sharing p*rn and selling drugs are popular pastimes online - not exactly breaking news. And definitely not a transparent window into the machinery of these big platforms.

Starting by asking how much content gets removed is the wrong question. It may be helpful to track this continuously, and give out punitive fines if harmful posts are missed or to investigate when the numbers change significantly.

But the actual window into how large UGC platforms work is what the policy and comms teams have been discussing in any given month. What are the hot topics they're grappling with, the edge cases flagged for further consideration? These conversations and debates provide a much more transparent window into how a platform operates and whether there's clear leadership and commitment to creating "safer digital spaces" (the Digital Services Act’s stated aim).

Sometimes, a discussion prompted by a news cycle highlights a weakness in policy that needs addressing. Other times, there are edge cases that require a judgment call by someone senior. These conversations would be much more instructive to EU policymakers, spotting areas where a platform is struggling to enforce its own rules or where a lack of clear rules results in muddled thinking and poor decision-making. But of course, having regulation in place is one thing. Having enough resources in place in regulatory bodies to effectively enforce those regulations is another. Hence, we end up where we are, with significant numbers that sound good on paper but don't speak to the broader, critical issues at play.

Issues such as a distinct lack of understanding of TikTok trends in the media, leading to a crazy news cycle claiming that teenagers were widely sharing Osama Bin Laden's "Letter to America" (they weren't, and if you want more on this topic, you should check out

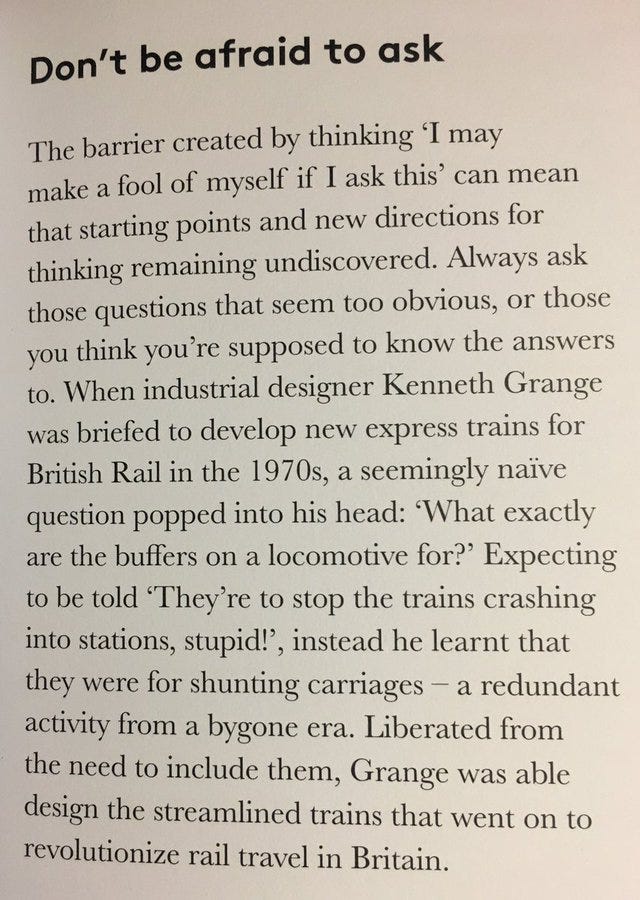

's definitive piece). Or the fact that we all assume that the Chinese government probably does take an active role in deciding what's appropriate for TikTok, but there's no definitive way of proving that. Or the psychological factors behind why so many young men find comfort online in group misogyny and hate speech. You can probably think of other issues that intertwine to make large online platforms feel like unsafe digital spaces. The common thread is that the DSA, based on the information we've seen so far, isn't set up to tackle any of these issues.To be clear, I’m not against regulation. These issues are all incredibly complex, and making safer digital spaces was never going to be easy. But one of the best ways to start any endeavour, whether a campaign response or investigations into online safety, is to ask the right questions. Make sure you're asking both the difficult questions, and the obvious questions that you might feel a bit silly for asking.

There is no such thing as a stupid question, and what you might think is an obvious question with a simple explanation can provide a surprising answer that becomes a new jumping-off point. Or answers that highlight a lack of clarity or consensus within the organisation you’re quizzing. Better questions mean stronger foundations for your thinking - stronger foundations generally produce better results.

So, to paraphrase Sex And The City for one final time, I couldn't help but wonder - should we be asking very large online platforms how much harmful content they remove every month, or should we be asking ourselves why people share and sometimes seek out such harmful posts? Our desire for transparency risks not creating safer digital spaces, but a whole bunch of PDFs that no one apart from me will read.