Selling out used to be a big deal in the world of music. Bands and artists that signed for major labels faced accusations of "selling out" - in other words, betraying the ideals of the independent music scene and taking major label money.

Even though plenty of well-respected bands made that leap, including the likes of REM, Sonic Youth and almost every grunge band you care to name, it still carried a stigma. Selling out had connotations of diluting your sound, of giving up creative freedom and making compromises to try and get on MTV (when MTV still played music videos).

And as someone who has worked with major record labels, there are plenty of those creative compromises.

However, the central tension often came from challenges around scale. Bands love the idea of the indie scene, holding on to their principles, street cred and creative control. But all artists want to be heard (or seen or read). Indie labels historically struggled with distribution, promotion, and getting your music in front of potential fans.

That's why the lure of the majors remained so strong throughout the 80s and 90s (and why we saw the rise of the major-label-backed indie label - keep your cool without compromising your reach, by signing to Creation, supported by Sony).

Most creators crave fame - they might not want to be the next Taylor Swift, but plenty would love to build up a big-enough audience to make their creative pursuit their day job. And thanks to the rise of the internet and algorithmically delivered posts in particular, that level of fame is not the pipe dream it was in the 80s.

In many ways, the big social media and entertainment platforms are similar to the music industry's major labels in their prime.

There is only a handful of them; staff consistently move between those same companies; they use their financial clout to hoover up any fledgling independents, buying credibility and stifling contribution.

The critical difference, of course, comes back to scale. Major record companies had finite resources, limiting the number of acts they could sign in a year. Big tech platforms have no limitations - if you're generating enough views, you can start sharing in some revenue. Sure, only vanishingly few creators will get to Mr Beast's levels of fame. But that dream of quitting your day job is open to everyone. The audience is there; your job is to get yourself in front of them.

Of course, it isn't as simple as that, but that's the dream the platforms sell. “Your audience is waiting!”. It's also why, despite a raft of articles in the past few weeks suggesting the opposite, the “federated future” of the internet will struggle to replace what we have now.

As Twitter continues turning into an actual hell site (as opposed to an ironic one) and the other major platforms continue to dominate (half the planet uses one kind of Meta product), the tech blogosphere sees a future in returning to self-operated websites and social networks, all linked together by Web3 interoperability. The arguments are compelling - I remember it being all the rage at the last SXSW I went to in 2019. You're in control of the whole publishing experience - there's no third party changing algorithms and cutting you off from your audience. You're responsible for moderation and setting rules of engagement. You charge what you think your output is worth rather than subsisting on revenue share crumbs.

Even in 2019, I was sceptical. It's certainly, like the 80s indie label scene, an attractive idea. It's rooted in a clear set of principles and ideals. But, as David Pierce writes in The Verge, it's hard work. It requires the kind of technical knowledge that people working in or writing about tech either already have or love to build up through trial and error. It's not, as Pierce says, as simple as typing a username and password "into some Meta platform".

And that hard work isn’t limited to the people setting up their own websites or building their own social servers. As anyone who’s signed up to Mastodon knows, it takes time and effort to find people you want to connect with. It’s undoubtedly one of the factors that’s played into Mastodon slipping away from the front of the “Twitter alternatives” pack.

Making it difficult to both sign up to these platforms as a user and complex to join and manage as a creator automatically puts a limit on the potential scale for this “new internet”. It’s spaces for those tech early adopters, the people who are already on Bluesky, who wax lyrical about the glory days of Twitter (2009 - 2012ish).

That’s still an estimated 1.8 million users (current Bluesky user base), so it's not insignificant. And that kind of structure provides the room for the scale that most people (including me, ha) would be more than happy with. But it’s not chart-topping, YouTube front page levels of scale.

Like those independent labels of the 80s, what you gain in control with a federated, DIY social network, you lose in terms of reach and distribution. Without the network effects and discovery capabilities of prominent social media platforms, it's much harder to reach a critical mass.

It’s also generally more complex to build up an audience without the aid of those in-built recommendation engines. It certainly feels true of my Bluesky experience so far - finding people to follow requires more time and effort than I can, frankly, be bothered to put in. LinkedIn is just easier.

And I consider myself relatively tech-savvy. If I find it an arduous task, there’s no way that social media users in the real world (i.e. outside of the early adopter tech/media bubble) will convert. TikTok serves you videos without you even having to log in. The DIY internet can’t compete with that.

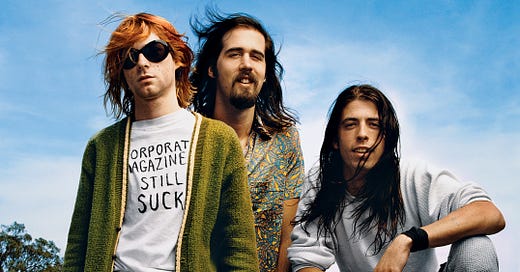

Of course, competition isn’t the point here - just as it wasn’t the original point of the indie label scene. The point is providing better options, more choices - showing people, to quote Kris Novoselic, “that's there more out there than just these mainstream, giant, Harley-riding rock bands”. There is an alternative.

Better alternatives certainly present more options for people working in comms. Under this DIY approach, you can imagine a growth in the communities of interest that already exist in pockets of the internet. The Discord servers and giant WhatsApp groups that serve specific purposes are of great interest for planning purposes. If they continue to proliferate, they will be even more interesting, particularly if we can map those communities of interest over “stakeholder”-type audiences, like investors, analysts, policymakers, etc.

Like those indie records you’d read about in the NME, they’re much more challenging to find, of course. A Brandwatch query won’t help you find these places automatically; they won’t be called things like “Thai food near me”.

The MIT Technology Review piece I linked to talks about “How to fix the internet”. That’s the wrong framing - it’s not about the indie scene replacing the major labels. It’s giving people more, better options, so they don’t just have to default to giant platforms with questionable approaches to content moderation.

Sure, most people will stick with the big platforms and the potential for discovery, connection and revenue they offer. But who knows what kind of creativity and hidden gems might be unearthed from platforms where the algorithms aren’t gods? Those creators may need to eventually “sell out” to get where they want to go but do so on their terms - retaining that creative control and staying in charge of their destiny.