Talking 'bout those generations (X, Y, Z)

Each new 'generation' brings the promise of progress - but it's an illusion we need to look beyond to find real change.

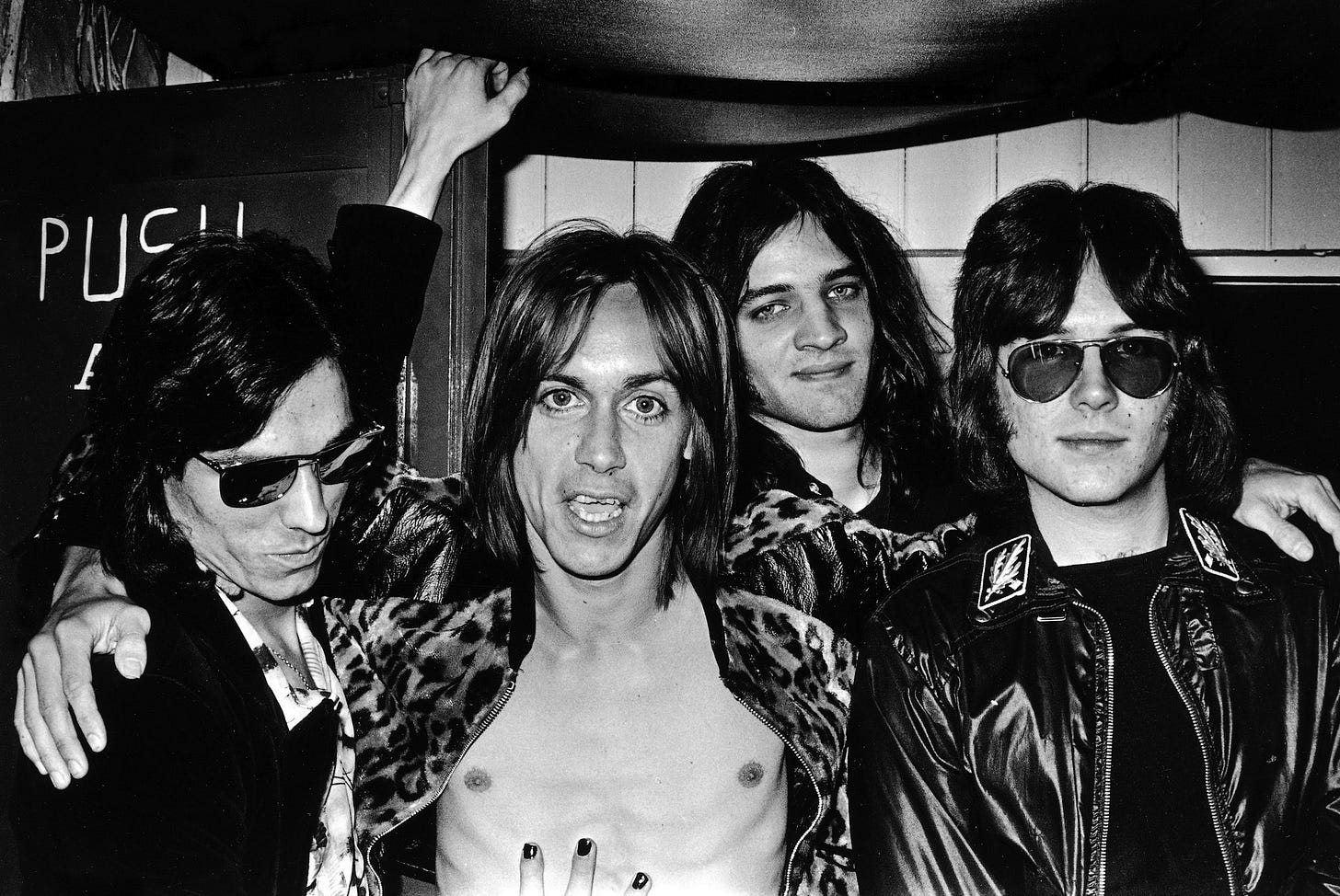

I’ve been stuck in the late sixties lately. Watching Gimme Shelter, the brutal documentary about the Stones' ill-fated free gig at Altamont; reading Please Kill Me (courtesy of my brother), an oral history of punk that starts with Andy Warhol and The Velvet Underground in late sixties New York; and enjoying Jim Jarmusch's excellent Stooges documentary, Gimme Danger.

All three attempt to capture one of the pivotal moments in US cultural history - the point where the "dream of the sixties" died. Altamont is the starkest 'moment' where the hippie ideals of peace and love come up against stark reality and human nature. But there are others - the MC5 playing during a riot at the Democratic convention in 1968; the reliance on drugs like speed and heroin that don't blend well with the much-mythologised ideals of the 60s.

Clearly, this period represents a pivotal moment in US history; like we've all experienced over the past three years, the late sixties packed a lot of history in. But while, as human beings, we like our stories this way - simple, easy to understand, with clear cause and effect on display - the reality is often very different. There's no one moment when the 60s ideal of peace, love and freedom disappeared. Plus, those ideals were not reflected across the broader US population - according to The New Yorker, 88% of 21 to 29-year-olds HADN'T smoked marijuana in 1969 (or weren't willing to admit it to a pollster). Three-quarters weren't in favour of an immediate withdrawal from Vietnam.

Cultural changes happen slowly and then seem to take place all at once. Our narrative of generational change and conflict interweaved with simplistic summaries of decades (the 60s = peace and love; the 80s = greed and shoulder pads) obscures the myriad experiences and events that make up our shared history.

It's also vaguely amusing to think of decades having sharp boundaries - that overnight we went from shellsuits and perms into baggy jeans and floppy fringes when the year ticked over from 1989 to 1990. There's so much bleed between eras; you can only see this bleed and the slow winds of change from a decent historical distance.

But still, we use the decade as a marker of time (I am a massive fan of them), alongside those companion definitions, the "generations": baby boomers, Generation X, millennials and Generation Z. You can read any number of pieces on why using these terms is an exercise in extreme folly. My favourite in this genre is BBH's "Puncturing the paradox: group cohesion and the generational myth", which makes the simple but devastating point that any group that includes both Prince George and Lil Pump, and says "they're similar" is faintly ridiculous.

And yet - these terms persist. What's their appeal? By any objective measure, talking about groups of people connected by nothing more than the year of their birth falling within the same 15-year timeframe as if they're the same makes no sense.

Their appeal comes with each generation bringing a new promise of seismic change - a tantalising prospect on many levels. We get excited about the potential of a new era, with fresh attitudes and new ideas coming along, and solving the deep-seated societal issues that the rest of us have given up any hope of fixing.

I was the same with Gen Z - during my last trip to SXSW in 2019, I saw a few teenage/early 20-something speakers - including Nadya Okamoto, founder of PERIOD, and Ethan Sonneborn, who ran for Governor aged 13, and got typically frothy and excited about what giving this new generation a voice could achieve.

My favourite quote was, "We don't want a seat at the table; we want to flip the table". Yeah, man - that's the punk rock, rock 'n' roll spirit the world needs right now. Iggy, Lou and Keith would all definitely approve.

The trouble is, like most things in life, the new spirit of Gen Z isn't actually new. Even a cursory glance back at the headlines around Generation X (technically my own cohort, in case you were wondering. It's certainly one of my favourite books) reveals similar excitement: "Slackers? Hardly. The so-called Generation X turns out to be full of go-getters who are just doing it—but their way."

Thanks to The New Yorker, we can go even further back, to 1967 and that famed summer of love, to find some excitement that's bubbling over it's so frothy: "There is a revolution under way . . . It is now spreading with amazing rapidity, and already our laws, institutions, and social structure are changing in consequence. Its ultimate creation could be a higher reason, a more human community, and a new and liberated individual. This is the revolution of the new generation."

These days Baby Boomers (arguably the most American of all the generational terms) are derided for being luddites who hoard money in their expensive houses. 50 years ago, they were the future. The same fate awaits Gen Z - media and comms people give too much weight to generations, or what sociologists call "cohort effects...change that results from shared generational experiences."

We underweight the other two explanations for how people's attitudes and behaviours change - mainly because these two, like all the best trends, are slower and harder to notice on a small scale. They are period effects, representing societal shifts, such as the effects of the pandemic we're living through right now. And also, there are lifecycle effects, which are the changes that individuals go through as they get older. The three types of effect also affect each other - there's evidence to suggest that the trend of people getting more conservative as they get older is waning in our modern age.

The challenge for those of us working in marketing and communications is that terms like millennial and Gen Z distract us from the slower, more interesting trends we should be paying attention to. The charts that don't change, as BBH calls them. There's a tendency to think that by appealing to that new generation, brands and businesses can absorb some of that revolutionary, table-flipping spirit by osmosis. Get Gen Z on board, goes the McKinsey logic, and suddenly the image of your business will look way cooler.

Appealing to the so-called Gen Z won't change anything about your business. It's an exercise in futility because it doesn't exist. Most young people don't seriously describe themselves this way - Gen Z is a term like Britpop or grunge; it's a useful media shortcut that individuals strongly reject. It's been around so long now it's essentially meaningless - the bracket of Gen Z starts around 1997, so the oldest members of this cohort turn 26 this year. That's not so young, even in our era of delayed adulthood.

We must forget Gen Z and other meaningless generational terms when considering audience profiling and comms briefs. If we want to change how people see a brand, we need to understand our audiences more deeply and more sophisticatedly. We need to know who our advocates are, our detractors, and most importantly - who are the swing voters? Where is the middle ground that represents our potential winning territory? Understanding those people - their differences and commonalities - is crucial in developing campaigns that demonstrably impact brands' reputations.

Defaulting to generic terms like Gen Z will likely only provide generic campaigns and generic, run-of-the-mill results. Enjoy as many media articles as you like about generational conflict, but make sure you enjoy them with a critical eye - and mercilessly interrogate them if they end up in a brief that comes across your desk. Like the dream of the sixties, the dream of distinctive radical generations has never been real.