Modern Britain is rubbish

New research published by Dazed highlights the complex relationship people have with their national identity

The thing that first attracted me to Succession was the fact that its writer is British. And watching it made me think, "How on Earth did the guy who wrote Peep Show, one of the most quintessentially British shows, end up making this portrait of New York high society?"

We often see traits and trends in others that we miss in ourselves because we're more objective in those third-party views. As the cliche goes, we find it easier to advise others than ourselves. Jesse Armstrong's outsider view of the 1% is cold and unflinching; it's the polar opposite of the warmth with which he celebrates the quirks and oddities of British life in Peep Show.

That may speak to a particularly British humour that Peep Show captures perfectly. It's the type of humour that leads people to say that being British means “being a twat” - a beautifully concise response to a recent Dazed survey on British identity.

That survey, part of Dazed's Horror Nation series, found that one in five “young people” (their definition, not mine) felt proud to be British. And the top things that contributed to this pride and enjoyment in their country were our humour and our culture, particularly music. Elsewhere among the qual responses, people pulled out roast dinners, Nando's, and, yes, Peep Show as being emblematic of Britishness.

Given it's an almost impossible task to define "Britishness" and modern British identity, centring a response on humour and the age-old tradition of taking the piss ("being a twat") is a strong place to build from.

I imagine you'd scoff at the task if someone briefed you to develop a pen portrait or audience persona of "the British" as your target demographic. It's bad enough making sweeping judgement statements of huge and diverse demographics like "mums", let alone performing that same exercise for a whole country.

And yet still, people try to sum up this little island in that way. To boil down the essence of 67 million people into a few sentences. And then, when this proves impossible, publications like Dazed come to the unsurprising conclusion that "evidently, Britishness isn't straightforward". Any definition of Britishness would need to take in hundreds of years of history; reckon with our history of slavery, imperialism and racism; and cover a vast diaspora of socio-economic backgrounds, ethnic diversity and divergent political viewpoints.

You'd be at dissertation length before you even got started. Indeed, my own dissertation focused on British identity, and I was only considering it through the lens of three early 90s novels (London Fields, Fever Pitch and Marabou Stork Nightmares) and their associated cultural milieu.

Even though the gap between Dazed's report and my dissertation is over 20 years, both focus on the same topic - how British identity exists in a perpetual state of flux. And that this flux is driven by the disparity between the image of Britishness, as marketed to the rest of the world or weaponised in political rhetoric, and the day-to-day reality of living in this country.

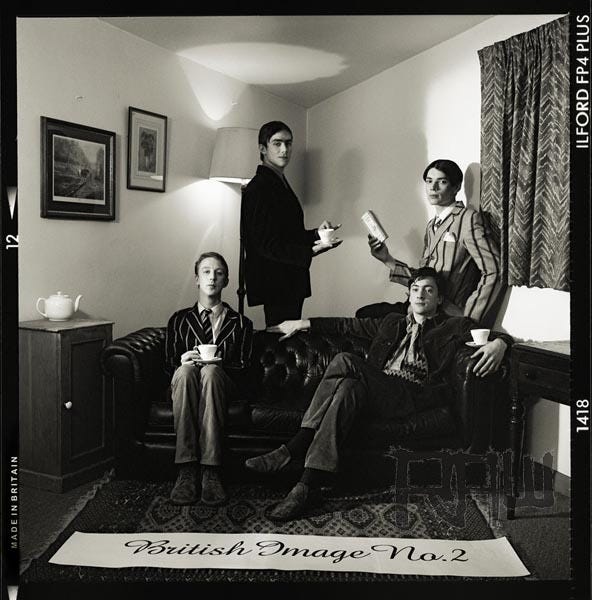

In the 90s, the dominant cultural forces were Britpop and Cool Britannia - packaging up the largely male, white artistic products of the time into a zeitgeist that directly recalled the 60s - another much-mythologised period of British culture "ruling" the world.

In the 2020s, the image we're selling is of a country freed from the strictures of the EU, taking back control and setting our own agenda. A petri dish of technological innovation, leading the way on AI. Returning to growth and "levelling up" the country.

Both now and in the 90s, the image of the country is a long way from the day-to-day realities of most British people.

As films like Billy Elliot and The Full Monty showed, the scars of unemployment and Thatcherite economics ran deep into the 90s; as great an album as Pulp's Different Class is, it'll never paper over these large cracks in society.

In the 2020s, people feel "disappointment, shame" about their country. Being British is "a daily embarrassment", largely driven by dissatisfaction among young people with the government. The disparity and conflict between images of Britishness and the day-to-day reality of living in this country are even more acutely felt by those from different ethnic backgrounds. "I am a British citizen, however my ethnicity is not British. I feel lost, as I am not connected to my ethnic roots, however I don't feel British either," said one respondent. (For more on this topic, I highly recommend Nikesh Shula's collection of essays, The Good Immigrant).

Any attempt to define Britishness and what it means to be British is doomed to failure because it's only ever a cheap caricature of what it's like to live on this contradictory, endlessly piss-taking, conflicted island.

And while Dazed's Horror Nation survey is a timely temperature check on how "young people" feel right now, none of the findings should surprise anyone working in comms. The conflict, the dissatisfaction, and the disparity between wider society and lived experience have been key features of many reports over recent years. Britain Thinks' Mood of the Nation series captured this expertly, while More in Common's Britain's Choice report showed how closely these feelings map to people's values and core beliefs.

When planning and executing campaigns, we need to keep this temperature check of our specific target audience in mind. We need to understand how people tell us they're feeling while carefully monitoring their actions. Identifying and understanding gaps between intent and action; looking at the disparity between the persona people want to project online and the reality of what they have in their kitchen cupboards (to steal a tactic from the excellent

project). Because you can think that the country you live in is "shit, nothing else" (to quote Dazed's survey again) and still love it dearly. Sort of.As Joel Golby put it in an old Vice piece (written in 2015, pre-Brexit): "England is a shithole. But it's our shithole." That’s probably as close as we’re likely to get to answering the brief of defining Britishness - and it doesn’t even mention Great Britain. Let’s leave the pointless pen portraits of what it means to be British to those looking in from the outside. On the inside, we’ll revel in the reality of the highs and the many lows, and look to make the best of the hand we’ve been dealt. And so what if we don’t really love our country? As Mark says in Peep Show, “Charles didn’t really love Diana and they were alright. Sort of.”