Illusions of community

Meta talks about its users as a "community", even as those users number 3 billion. It's a frankly ridiculous concept.

When I was helping manage the comms for one of Meta’s big three platforms back in the day, I learned a vital client mantra. We never, ever referred to people who used the app as “users”. They were our “community” (and variations thereof). Users made it seem like we didn’t care; community reflected the welcoming spirit we wanted to project.

It’s a standard PR tactic - framing your communications to deflect accusations of being an evil, faceless tech company. At the time, I never considered the ridiculousness of calling a user base of 1 billion people a community.

Luckily, I don’t have to turn a wilfully blind eye to such ridiculousness these days. Mark Zuckerberg, on the other hand, is still in that space. During his interview with The Verge, Zuckerberg referred to Facebook users as “our community”, an even more patently ridiculous notion given that Facebook’s MAUs equate to over a third of people on Earth.

Zuckerberg used the term as part of a broad brushstroke response to news organisations asking for payment for the content they publish on Facebook:

On the other hand, we have our community, which is asking us to show less news because it makes them feel bad.

It’s certainly true that there is a global trend towards news avoidance because of, as Zuckerberg alludes to, the grim, unrelenting state of current affairs.

But it is still quite the power move to boil down the user behaviour of such a vast number of people (even accounting for a percentage of fake and sock puppet accounts) to a simple binary decision.

Instagram head Adam Mosseri used similar abstract language in a recent Q&A about the move from a “following” timeline to an algorithmically defined one.

Every time [we’ve tested a following-only timeline], there’s a sub-group of people who are happy, there’s a bunch of people who forget that they’re in it, and then overall, everybody who’s in it uses Instagram less and less over time, and when we ask them questions like ”how satisfied are you with Instagram?”, they actually report being less happy with Instagram more and more over time, on average.

There is brutal simplicity in the decision-making on show here. We hear complaints about timelines filled with algorithmic recommendations, so we test moving away from them. However, the numbers show people use Instagram less as a result, which is bad for business, so we focus back on algorithmic timelines.

Perhaps this is the level of abstraction and brutality required when you’re in charge of platforms with multi-billion-strong user bases. But it’s probably time to dispense with the pretensions of community and be explicit about the primary roles of Facebook and Instagram.

They’re low-friction video delivery platforms that focus purely on encouraging you to spend as much time on the apps as possible, maximising your exposure to advertising. You might argue that this has been the case for a long time, ever since Facebook added self-service advertising.

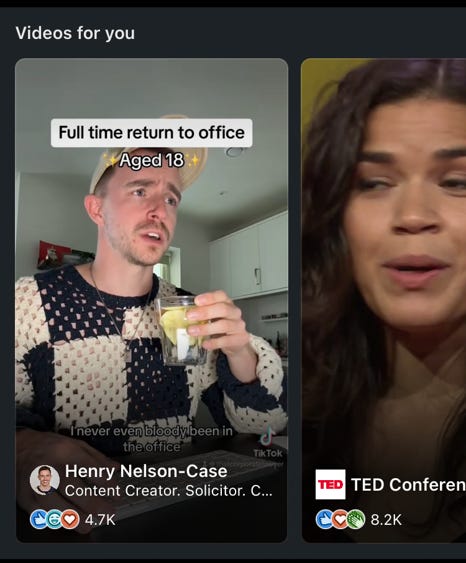

The difference now is that any pretence about “quality content” or “time well spent” is firmly out of the window. As Ryan Broderick pointed out in Garbage Day, both Mosseri and Zuckerberg now say the unsaid. The existential threat TikTok poses to Meta’s bottom line means they’ll do anything to keep you on their platforms - and right now, the surest way to do that is with algorithmically selected video.

It’s also further proof, as if proof were needed, that the ‘social’ side of social media is a purely one-way conversation. Facebook and Instagram “communities” exist to consume, to like, comment and share. Connection and dialogue are not for your feeds; they’re the sole preserve of Meta’s DMs, Groups and messaging apps. The feed exists, to return to the food metaphor again, to feed you videos and suggested posts.

But so what? Social media has been focused on entertainment for a good few years now. The continued democratisation of access to quality video creation tools, plus the incentives offered to creators for sharing Reels-type videos, mean the short, snappy vertical video is now arguably the lingua franca for much of the internet.

Even LinkedIn has a Reels clone, attempting to make a product out of the popularity of corporate videos which aren’t, like, regular corporate videos (they’re cool videos).

However, there are undoubtedly second and third order consequences to contend with due to these changes.

Much of the promise of the creator economy is built around developing a fanbase online. Social platforms like Meta’s offered more accessible pathways than the Noughties network of blogs and forums. But now, these pathways are less productive, given how posts from people you follow mix in with the algorithmic suggestions that aim to keep you hooked.

And creators feel that their reach numbers underperform unless they keep up with the latest methods for tickling those same algorithms. This feeling can lead to another blunt binary decision like Zuckerberg and Mosseri’s. Either plough your furrow and risk limiting your exposure; or play the game, chase the likes and the crumbs of virality Meta platforms offer. Which we also know is a route that can lead some creators to make some dark and perverse choices.

And it’s not just online creators who feel this pressure to play the game and chase the benevolence of the algorithmic overlords. As Thea Lim writes in The Walrus, anyone creating some form of art for a living feels the pressure of quantification.

In many respects, this is nothing new. As Lim says, there’s always been a tension between the creative process and the need to sell your creative output. The worry is that obsessing over the quantification of your work overtakes your enjoyment of the creative process itself. That writing or storyboarding with the objective of likes and virality in mind overweights the commercial side of creation, simultaneously ramping up the pressure and sucking the joy out of the process.

This leads us back to another potential consequence of Meta’s definitive move away from the social graph - the increased homogeneity of what we see in our feeds. If we’re all chasing the same algorithmic favour, based on the same guidance shared by the likes of Mosseri, we could end up with feeds that look the same and feel bland and repetitive.

I’ve spent some time exploring LinkedIn’s new Reels clone, rolling out as part of the app. Admittedly, it’s new, so it will need time to attract a variety of videos. But my feed was already full of variations on a few themes - that weird, monotone TikTok voice over green screen backgrounds; podcast clips cut for vertical video; Rob Mayhew and then Rob Mayhew-style imitators. Slightly different from Reels and TikTok, but not markedly so.

I actually don’t tend to think that homogeneity is the real problem we face. People who use big video-sharing platforms are endlessly creative, and I’m constantly amazed at how the creative constraints of a 60-second vertical video can produce endlessly imaginative results.

I think the real risk is the accelerated copycat-ing when a new video style becomes popular. We’ll see microtrends burn brighter faster than ever, with that speed only accelerated by genAI video tools. There’s enjoyment to be had in the lifecycle of a trend, seeing it bubble up, reach critical mass then die away as the brands get involved (Deutsche Bank doing Brat summer, for example). I can’t help but wonder if the cycle will feel so enjoyable when it happens in a matter of days instead of a matter of weeks.

I don’t do advisory work on any of Meta’s platforms anymore, but if I did, I would strongly suggest they drop the “community” pretence. While community has always been a diffuse and slightly meaningless concept for huge, feed-based platforms, it has arguably now been replaced by fandom in most contexts. It is almost entirely redundant when we look at how those same big Meta-owned content sharing platforms work.

Viewers exist to consume and to provide essentially binary feedback to creators and machines - more of this and less of that. That same feedback loop applies to brands and businesses as well. Outside of employees and alumni, your engagement on social platforms is fleeting and invariably driven by paid social media to ensure you reach the people you need. Communities may exist and indeed flourish in other internet spaces, even in different parts of Meta’s empire. However, the idea of what you see in your newsfeed and the brands you follow representing something more meaningful than entertainment is stuck in the early 2010s.