Harnessing attention

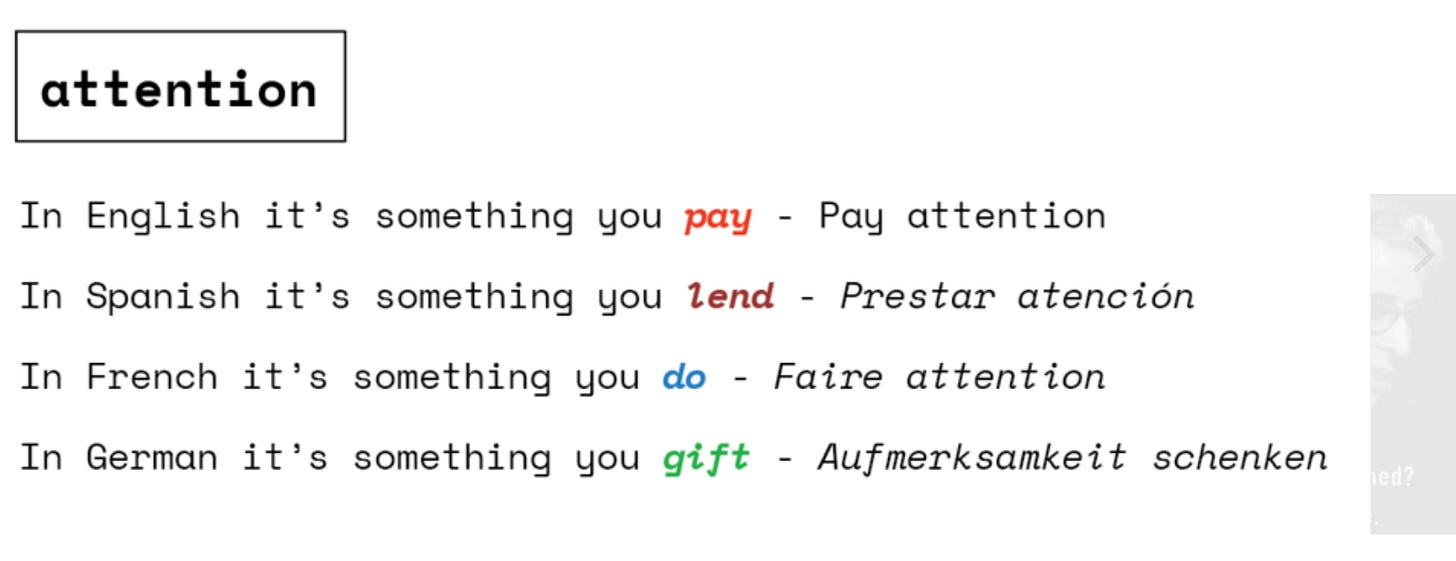

We pay attention in English. But what if we were more European, and started lending or gifting our attention instead?

I love words. I particularly love delving into the etymology of words and understanding their origins. But having spectacularly failed my German A Level, I’m only able to explore words in one language.

As a result, I often return to this piece by Juliana Castro in Are.na, where she unpacks the Latin roots of the word ‘attention’ and how those roots have evolved in different ways across various languages.

I found the action verbs that attention takes in other languages particularly interesting. We pay attention in English; it is something you lend in Spanish. In French, you ‘do‘ attention, while in German, attention is something you gift. While it’s a subtle differentiation, the way we use our attention - offering it out, using it consciously, or having it demanded of us (”pay attention to this next part”) - speaks to the multi-faceted nature of attention itself.

Unpacking attention and its various forms is crucial for comms in 2025. When so much of what audiences consume is via their smartphones, we focus on “capturing people’s attention” or “grabbing attention in the newsfeed”. It’s very aggressive language, and it speaks to the attritional nature of our work at the moment.

There’s lots out there to look at when we’re on our phones. For brands and businesses, they’re not only fighting against their competitors to have their paid posts appear in feed, but they’re also fighting for the time audiences might otherwise spend with The Rest Is Politics, Celebrity Traitors, or TikTok.

The advice from platforms and media buying agencies has been the same for many years: to successfully capture attention, put your logo upfront, make shorter videos (and when they say short, they mean 10 seconds), and place the most impactful shots at the start.

There is a widely held view that our attention spans are shorter than ever, primarily due to the amount of time we spend on social media and on smartphones. Best practice suggests leaning into short attention spans and capturing those precious few seconds with concise, “snackable” posts and ads.

But what if we’ve been thinking about attention all wrong? What if, in trying to capture people’s attention, we’re missing a trick in not taking into account the fundamental nature of our attention?

The most common root for the belief that our attention spans are shorter than ever comes from a series of media articles published in 2016. The reports revelled in the news that our attention spans had dropped from 12 seconds in the year 2000 to eight seconds now. We’re goldfish, lol, etc.

Thanks to some BBC investigative reporting, there is no reliable source for this eight-second figure. The very concept of an attention span itself is something that many academics question. Attention is “very much task-dependent. How much attention we apply to a task will vary depending on what the task demand is”, according to Dr Gemma Briggs from the Open University.

Another widely cited study, published in 2019, showed that trends burned brightly but faded more quickly than ever. The study utilised a diverse range of sources, including data from Google Trends, Reddit, and Twitter. The headlines that accompanied this research highlighted that our “global attention span is narrowing”, aligning this latest study with the previous eight-second statistic and reinforcing what I will call “the goldfish misnomer”.

Rather than leaning into the goldfish misnomer and making everything shorter, comms practitioners must explore the “task-dependent” nature of our attention that Dr Briggs mentions. Based on my own experiences (yours may differ), my attention fluctuates throughout the day. Some things require my full attention, while others do not - particularly tasks that you are intimately familiar with.

My daughter loves the book Sharing A Shell, and I’ve read it so many times that I pretty much know it word for word. A consequence of this is that I find my attention drifting away from Crab, Blob and Bristelworm’s antics and onto other things.

Similarly, you might drive home on a route you’ve used a thousand times over and have very little memory of the journey. It’s not because you weren’t paying attention; it’s because you know it so well that the intuitive, reptilian part of your brain is in charge and doesn’t feel the need to make the journey memorable.

So the question for us as comms people isn’t necessarily just “how are we going to capture people’s attention?” We also need to consider the kind of attention we ask our audiences to lend us. It may be that if we’re looking to reinforce existing perceptions and maintain an image, shorter, snappier and familiar works. In that instance, playing to our intuitive minds would be sensible.

If we’re looking to change hearts and minds, we need to ensure we design campaigns to cater for a broader range of attention. And in particular, we need to think hard about how we can encourage audiences to gift our clients their full attention; how we earn the critical, conscious part of their brain that actively considers what they’re watching/reading/listening to. It’s no mean feat, but we know that audiences will spend their time on a thought-provoking, attention-grabbing story.

If changing hearts and minds is our goal, we should arguably start our planning with our audiences, rather than starting with our key messages or a laundry list of proof points.

We need to know what the people we’re trying to reach currently spend their precious time and attention on. What do they read, what do they watch, what do they listen to? And not just “67% of CEOs subscribe to the FT’s daily briefing email” (I made this statistic up), but which articles or columns or parts of a podcast do they never miss? Then we can learn from that information and use it to inform how we plan our clients’ campaigns. We often talk about meeting people where they are; maybe we need to meet them where they are, armed with a compelling package they can’t help but lend their attention to.

Arguably, our goal should be to take more care of other people’s attention. To focus as much on encouraging audiences to spend their time with campaigns and stories as on trying to capture people’s attention. And also not just to capture audiences’ attention, but to consider what we do with that attention once we’ve caught it.

We’ve got your attention. Great! Now what? That’s what we need to get better at understanding.