Curation and the joy of constraints

On switching up your playlists (and your thinking) to focus on 'less is more'

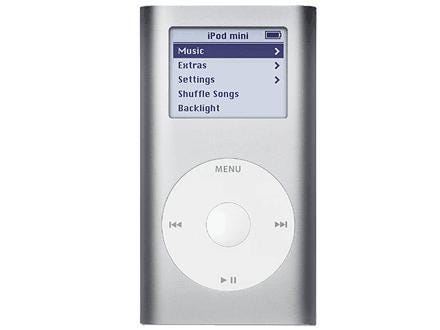

I first got an iPod back in 2004. It was a silver iPod mini with 4 GB of storage. It was incredibly exciting - my music-on-the-go choices no longer limited to the number of CDs or minidiscs that I could carry in my bag.

It also had another delimiting effect - compilations and mixes were no longer bound by the physical limits of recorded media (between 74 and 90 minutes, depending on the medium).

My playlists could stretch out with creative freedom - a collection of the best songs from 2005 covered 80-odd songs, instead of 24 across 90 minutes. My selection of the “best of” Nirvana no longer called for a decision between Pennyroyal Tea or Sliver; stick ‘em both on! Plus all the B-sides!

But a curious thing happened over the years. As the rise of Spotify made the choices even more unlimited (stick all the great unreleased Nirvana songs on the best of, too!), I began to crave the limits again. I’d get bored of listening to the Nirvana best of after an hour, and struggled to understand why.

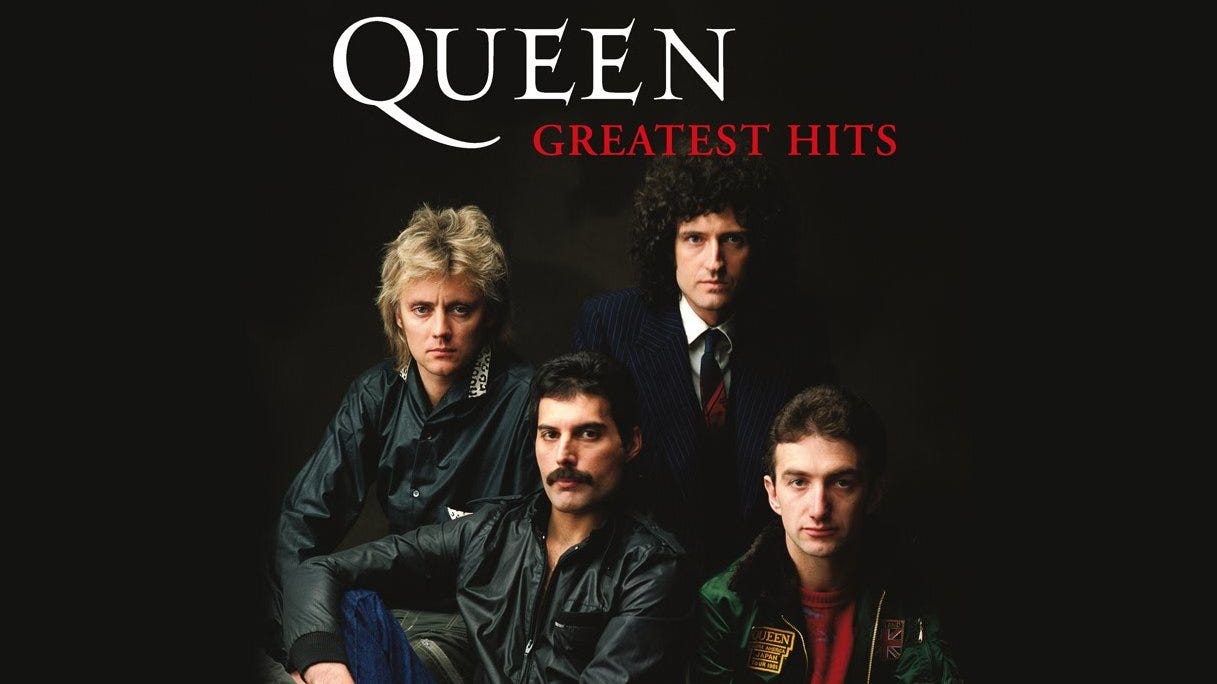

Then I read this excellent piece in The Guardian (which I may have linked to before). It highlights one of the reasons that Queen’s first Greatest Hits album (a staple of car journeys of my youth) was one of the best-selling albums ever.

It’s so popular because it’s a masterclass of curation. Greatest Hits and “The Best Of…” often default to putting all the songs in chronological order (my playlists generally did). Or they stick all the hits up front, knowing they’re the only reason people listen.

Greatest Hits does start with Bohemian Rhapsody, but it works. The overall flow is also impeccable, before finishing up with We Will Rock You into We Are The Champions (a fine example of, as Rob Estreitinho memorably wrote, starting strong and then letting your ending linger).

Listening back to Queen’s Greatest Hits made me re-evaluate my relationship with some of my playlists. I started to artificially recreate the constraints of physical media in my Spotify listening.

I purposely limited mixes to 90 minutes, forcing myself to make those tough decisions about what deserved to make the cut. I also spent time on the best order, creating peaks and troughs of mood and pace.

I even, for one playlist compiled in the depths of the pandemic (titled “Can We Panic Now?”, a companion to one developed in March 2020 titled “Don’t Panic”), experimented with putting a silent track of 30 seconds between two 45 minute halves, to artificially replicate the experience of turning a tape or record over. This experiment didn’t last, as I became paranoid about “30 seconds of silence” becoming my most played song in my Year in Review.

Clearly, these artificial constraints aren’t always necessary - playlists for parties and BBQs need wall-to-wall, back-to-back bangers. Sometimes when I’m working, I just want to stick something on and forget about it - a few albums of a certain type (post-rock, Daft Punk) queued up to play in that liminal space between the background and the foreground fit perfectly.

But my default mode when creating a new playlist or mix is to focus on curation, careful selection, and specific ordering. The end product, particularly when it comes to those “Best of” playlists, is markedly better.

The judgement call comes in knowing when the curation is the thing, or when it’s about the exploration or when it’s about an explosion of activity. And that’s also a significant part of the strategic creative process.

When you’re starting out with a project or brief, the exploration is the thing. Ideally, you want your approach to be the embodiment of Spotify’s Discover Weekly, your Daylist, or the random radio that kicks off when you’ve played a few songs.

Given it has a tenuous Easter link, I played The Stone Roses’ I Am The Resurrection on my mother-in-law’s Amazon Echo in the kitchen on Sunday. It kept on randomly selecting songs, and we all commented on just how many bangers we were treated to as a result.

That said, the suggestions were what you might expect (The Verve, The La’s, James). For campaigns, ideally your research phase would be more exploratory and tangential, throwing up enough curveballs and rabbit holes to provide access to something unexpected.

The most important, and always the toughest, curation job comes when distilling down everything you’ve learned, everything you know and everything you (and the collective team working on the project) think into some kind of strategy or approach.

I mentioned Rob Estreitinho before, and I like his approach to this phase of a project: do your research, think about the challenge, then start mapping out your response (either writing or sketching). The bits of your research that stuck in your head will come through naturally. Any other pertinent bits you can slot where appropriate. Anything else you can discard.

For particularly complex briefs, you might want to set up your approach with a series of strategic choices to force agreement and consensus. Do we focus on audience x or y? Platform A or platform B? Is it too obvious and uncool to put Smells Like Teen Spirit on our best of Nirvana playlist?

Getting down to the nub of the challenge, being able to articulate your plan in one sentence is the playlist curation equivalent of picking the perfect set of songs to fit into your chosen time constraint.

Sometimes it feels impossible, but all you need is time, a team pointing in the same direction, and a strong sense of judgment. I managed to distil the music of the 90s into five songs recently, so don’t give up hope (although in hindsight, it probably could have done with some drum ‘n’ bass).

It’s also a necessary step for developing any creative brief. No one wants to read the creative brief equivalent of an infinite playlist. Keep it tight, make those judgment calls. Creativity always flowers best when there are constraints involved.

Generative AI is your friend when it comes to creative ideation: turn your strategy into a creative brief with a simple prompt, or get ChatGPT to critique your work and ask it to dial up the constraints or make the thinking more concise.

When it comes to presenting or pitching your idea, it’s all about the playlist flow. As I mentioned before, take Rob’s advice about starting strong: “Make your first slide punch. Make your last slide linger.”

Don’t fall into the trap of trying to pack too many hit single ideas in a row - “and then we’ll do this, and then we’ll do that”. It’s too much, like a cake that’s all icing. Think about structure, about pace, about ebbs and flows.

The best pitches and presentations tell a clear story. They’re easy to navigate, with a distinct middle and end. Don’t finish on the budget (the audio equivalent of ending with a B-side). Think about Queen's Greatest Hits, Sgt Pepper’s, (What’s The Story) Morning Glory?. Give your audience something to remember: the comms equivalent of a tune they can’t help but hum.

Just because we have the option of including more in our work - more slides, more ideas, more research - doesn’t necessarily mean we need it. A smarter person than me wrote that you should always “write long and publish short”. You could adapt that advice for presentations (and playlists) to be “practice long and pitch short”. Your audience will definitely thank you for it.

I’ve included a link to my latest 90 minute Spotify mix to give you a sense of where my head is at musically right now. I particularly the love the last line of the last song - it’s the perfect way to finish in my opinion.