Believe in nothing

Thoughts on the gap between what people post and what they genuinely think.

According to psychologist Nick Chater, our minds are flat.

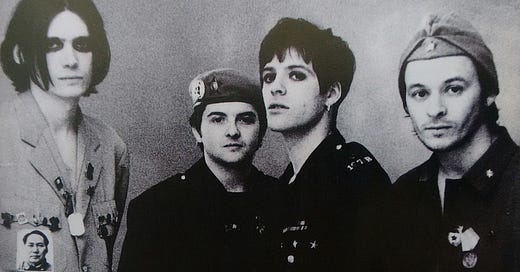

We’re all living embodiments of a famous line from one of my favourite Manic Street Preachers songs: “I know I believe in nothing, but it is my nothing”.

Says Nick in this Guardian article from 2018:

“The unfolding of a life is not so different to that of a novel. We generate our beliefs, values and actions in the moment. Thoughts, like fiction, come into existence in the instant that they are invented and not a moment before. The sense that behaviour is merely the surface of a vast sea, immeasurably deep and teeming with inner motives, beliefs and desires is a conjuring trick played by our own minds. The truth is not that the depths are empty, or even shallow, but that the mind is flat: the surface is all there is.”

(Nick’s book, also called “The Mind Is Flat”, is an excellent read).

Whether or not you subscribe to Nick’s theory that we act primarily based on situations and circumstances, it’s an apt framing to view much of the online discourse we see taking place in 2025.

Consider the case of YouTuber Cash Jordan, as reported in Slate last month. The headline of the piece says, “He used to make videos about NYC real estate. Then he became radicalized by the right.” The headline taps into the ingrained sense that we have innate belief systems, and the prevailing concern that those belief systems can be warped by what we see and read online.

The challenge is that we don’t know what Cash Jordan actually believes, just as we don’t know what anyone posting fringe, dangerous or hateful views online believes. It could be the case that Jordan truly believes New York is so dangerous that no one can live there. The likely truth, if we connect Nick Chater’s “flat mind” thesis with the uneven rewards of the creator economy, is that doesn’t truly think New York is that dangerous.

That’s because history tells us whenever an online creator suddenly pivots away from their original style of posting to something more dramatic, or radical, it’s because they’re unhappy with their visibility. And that stems from being unhappy with the financial returns from their posts.

And history also tells us that these pivots work. Look at Cash Jordan’s subscriber numbers and brand partnerships. The shift to alarmist, clickbait titles is clearly a lucrative one.

But just because the creator in question doesn’t believe what they’re saying, it doesn’t mean that their viewers won’t. While researching this piece, I stumbled upon a Reddit thread with someone asking why Cash Jordan pivoted his YouTube approach and whether his hyperbole was indeed accurate.

And it’s not just creates adopting this “sensationalism for cash” approach and potentially negatively affecting their audiences. We can also see elements of political discourse in the UK heading down a similar pathway.

A piece in Politico earlier this year highlighted that, in addition to dominating the engagement figures on X, Reform politicians are very much part of the creator economy:

“A scour through the MP’s register of interests reveals that the Reform lads have banked almost £20,000 from X since the election, with political novice — and Musk enthusiast — Rupert Lowe trousering nearly £8,000 from his posts, followed by Farage on around £5,500.”

Now, of course, it’s unlikely that Farage and Lowe will be relying on the revenue from their social posts in the same way YouTubers like Cash Jordan are.

But we know politicians want their thoughts and policies to be front of mind and front of paper. X may not have the cultural influence it once did, but the playbook of provoking a reaction to drive virality applies across all platforms.

And the worry is that the attempts to game those systems have become more and more extreme and have an even more significant negative effect on the discourse in the UK.

What’s clear is that unless the incentive structures of some of the big online platforms like Facebook, X, and YouTube change, the pathway to saying anything online for clout and cash will remain well-trodden.

For brands and businesses, the existence of this pathway heightens the need for the effective triage of posts when monitoring issues and crises. We can no longer assume someone is posting because they genuinely care about the topic. They could easily be picking on your brand or an issue associated with your business because of the potential virality it can drive.

So, how can you tell? Firstly, context is vital. Aim to understand as much about those targeting you as quickly as possible. Pay particular attention to their influence, followers and connections - is there anyone notable in their comments? Who have they been engaging with lately?

Look at their historical posts - do they have form in targeting brands and businesses in an attempt to whip up furore? Also, look at the topic that’s been highlighted; is it something that’s been covered before, and an individual wants to resurrect it for virality and financial gain?

We worked with a high street name last year who faced a similar attack from a couple of online videos. We found that the person in question referred to an article from many years ago, and attempted to surface it again to elevate their own profile. Knowing the historical context made triaging the issue much easier.

We can’t assume that every post is rooted in genuine belief; if we do, we risk taking performance for principle, and noise for substance. When so much online is performance, and we know that performance pays, our default position can’t be to take everything at face value.

It means we need to ask more questions, probe deeper, and examine the surface from different angles to see how it changes perspective. Just because it means nothing to the poster could mean everything to an audience. Knowing the difference is crucial.