The lottery was the subject of conversation on our pod this week. My colleague Simon used to work there - it was his job to persuade winners to go public with their winnings and do the classic photo with champagne and a giant cheque. Only around 10% of winners apparently decide to go public - most prefer to keep it to their immediate connections.

Simon also shared that by going lucky dip with your ticket, you were less likely to share your winnings with everyone - that’s because of our natural human bias for picking birthdays, so the numbers 1 - 31 will be stacked across other tickets.

Playing the lottery, particularly with a £200 million double Euromillions rollover, inevitably leads to daydreams of what you’d do with the money. I’ve written before about how I assume that when I buy a ticket, I’m going to win. Big questions crop up - How many guitars should I buy? Will I continue working? How much money should I give to friends and family? (Generally in that order, too.)

The friends and family point also came up in our chats with Simon - apparently, lottery winners tend to lose one close acquaintance post-win. Generally, it’s to do with a perceived slight over the amount of money they received.

You wouldn’t think becoming financially self-sufficient was a double-edged sword, but human history tells us we can struggle with our dreams coming true. There are a few compelling stories of lottery winners going off the rails. The tale of Aladdin and the genie looms large in the public consciousness, despite being at least 300 years old.

As The Pussycat Dolls sang, “Be careful what you wish for, ‘cause you just might get it”.

One such dream that remains desirable is that of becoming a famous musician or rock star. But just like lottery wins or finding a wish-granting genie in a lamp, achieving fame through your music is a decidedly double-edged sword.

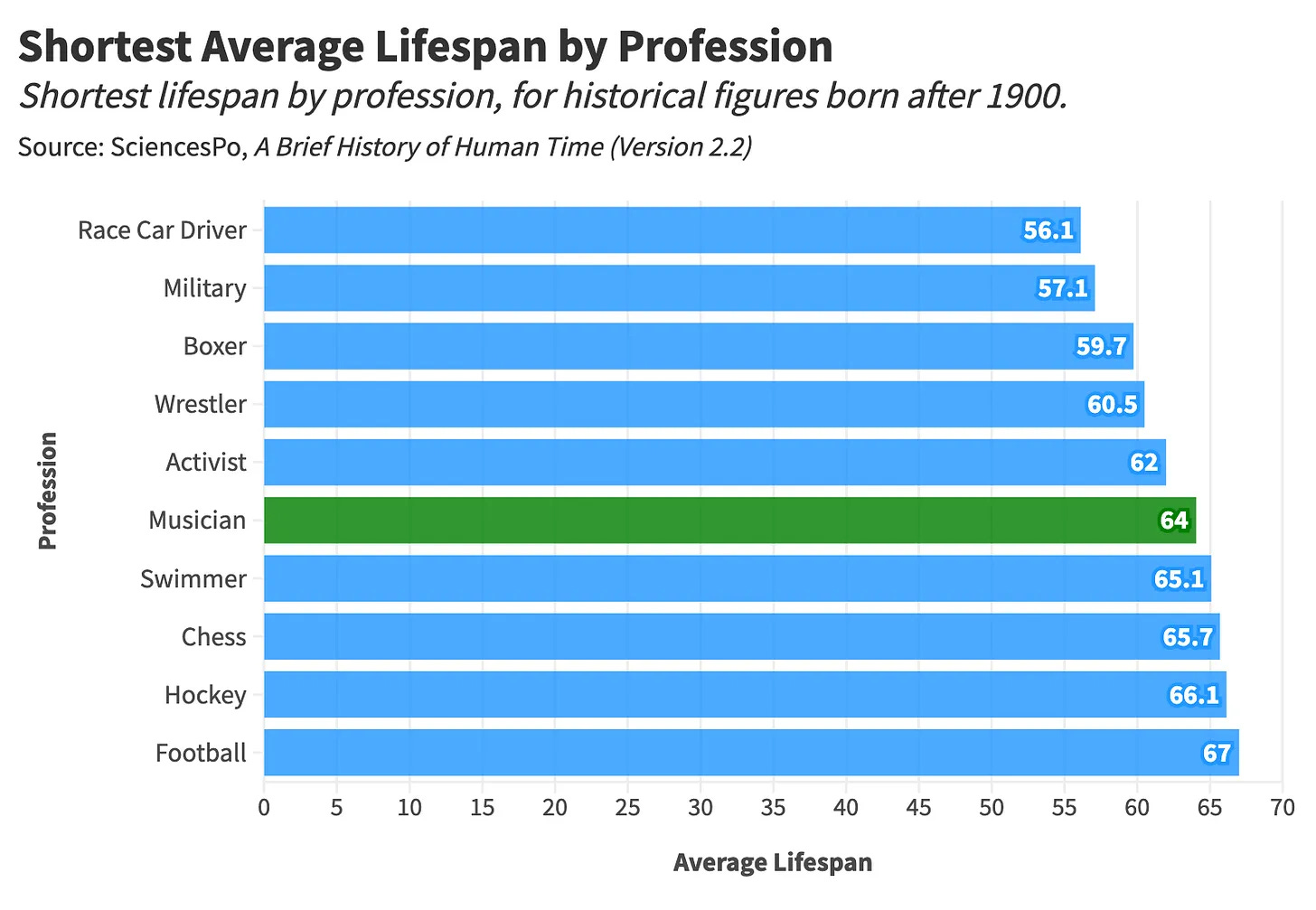

According to

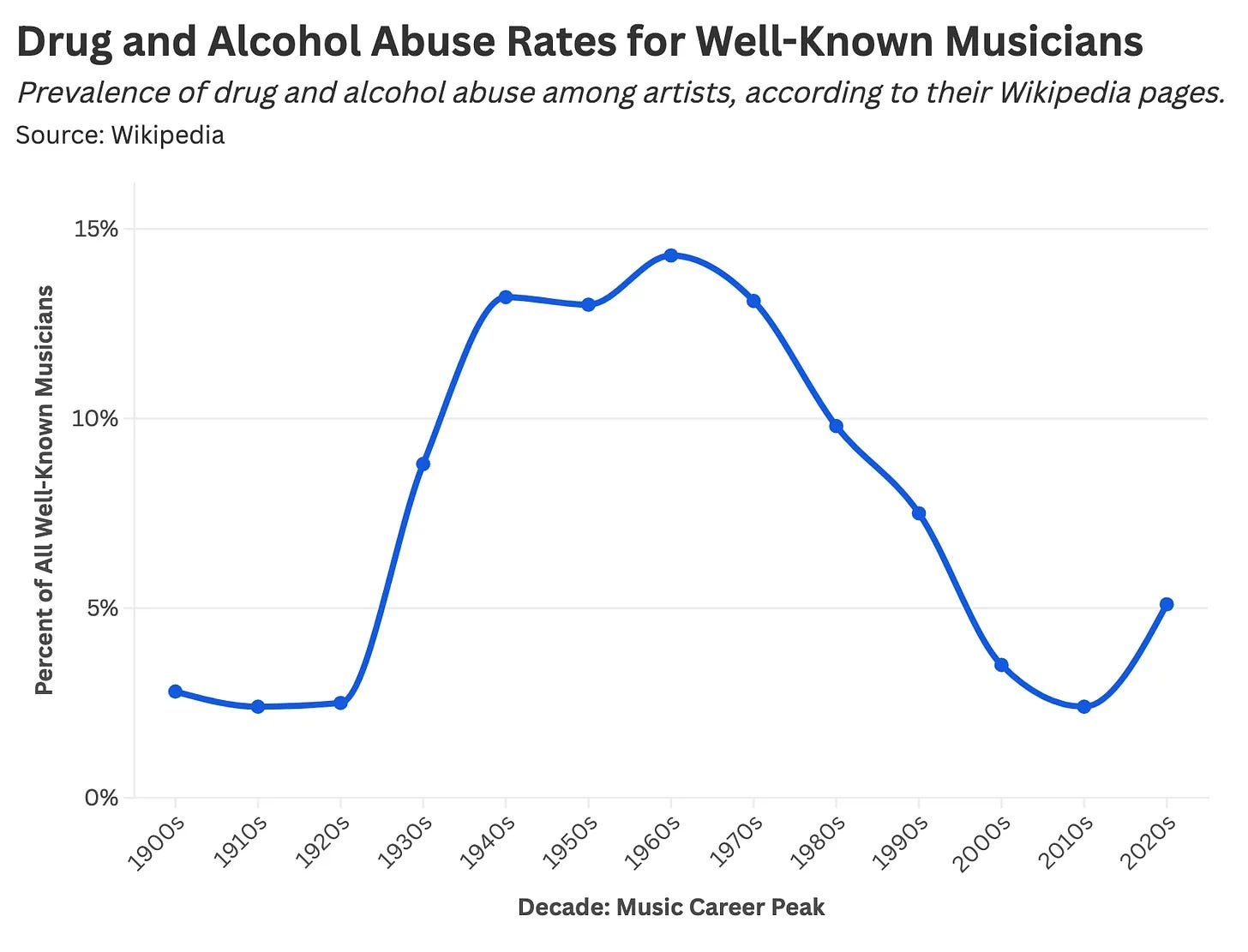

in the ever-excellent newsletter, being a professional musician offers one of the most statistically short lifespans, up there with racing car drivers, soldiers and boxers. Although confusingly, professional chess players also have a relatively short lifespan.Anyway, one of the primary drivers of these relatively short lifespans is the relatively high likelihood of a professional musician becoming addicted to drugs or alcohol at some point in their career. And while this might seem to be an outdated concept, the data shows this is not the case.

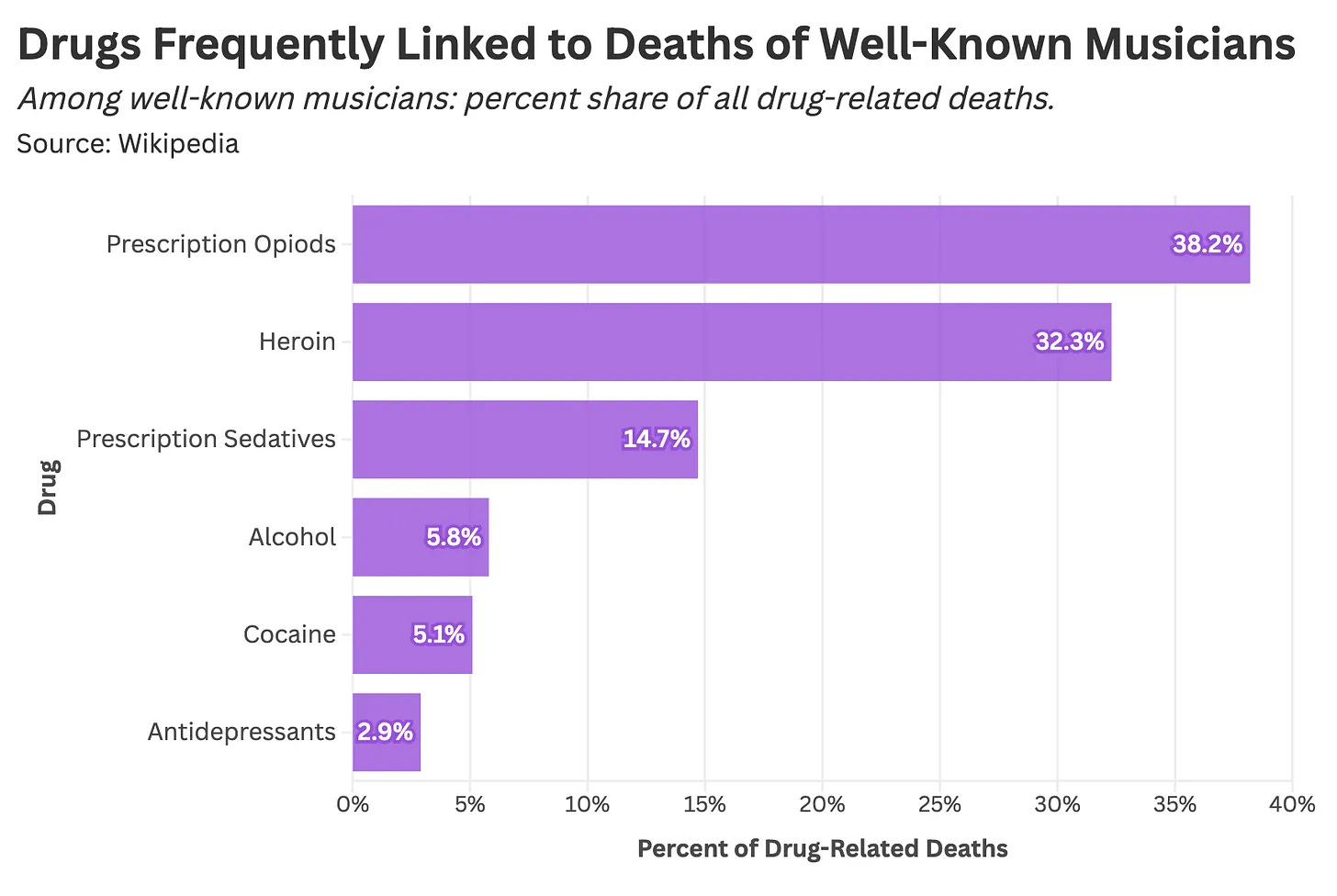

After hitting a peak in the 1960s, drug and alcohol abuse among notable musicians (those with a Wikipedia page) ticked upwards again in the 2020s. The addictive substance of choice changes over time, with recent high-profile cases sadly most often linked to the rise of prescription opioids in the United States.

It’s a sad state of affairs that being a famous musician, achieving one of the most unlikely of dreams, carries such a relatively high probability of addiction and premature death.

The analysis in Stat Significant is fascinating and robust, but clearly, there are a number of other factors behind the data, all complex and interlinked. Parris namechecks the recent Robbie Williams biopic and the way it dramatises the dehumanising effects of fame by portraying Robbie as a CGI monkey.

For rock musicians, a common thread I notice in the many music histories I read is the psychological effects of constant touring. The endless amount of time waiting around before a gig, the furious intensity of the show, then the comedown - the impossibility of sleep, the readily available substances. Then you do it all again, night after night after night.

For many artists, it takes a psychological toll - Bon Iver gave a revealing interview to The Guardian recently, highlighting how much more at peace he feels now that he no longer tours.

There’s often a duality at play here - like Martin Sheen’s character in the opening scene of Apocalypse Now, musicians desire and fear the highs of the show, interspersed with hanging around in liminal spaces. And given that many musicians tour to pay themselves a wage, there’s often very little choice.

But that high of playing is addictive - I only play my guitar at open mic nights where literally no one is listening, and I still love it. Imagine playing to thousands of adoring fans and generating that fleeting sense of connection through your music. For many people, it’s worth going through everything else to keep chasing that feeling.

The sword remains decidedly double-edged, and the decision for musicians is whether they feel the trade-offs and risks are acceptable in the pursuit of doing what they love.

We see those same double edges at play in other facets of life. While on holiday, and thanks to the recommendation by

in , I read Rachel Cusk’s memoir of motherhood, A Life’s Work (and I can’t recommend it highly enough). Cusk talks with refreshing frankness about her conflicted feelings as a mother of young children.The sense of having given up your previous, non-parent life, and her failed attempts to reclaim that life. The absolute desperate desire you have for your baby to sleep - and then when they do, you have no idea what to do with yourself, let alone sleep.

But that duality is arguably one of the cornerstones of parenting - you do everything you can for your child, so that they can be independent and not need you anymore. No matter how painful it may feel when they take even small steps to self-sufficiency, you must remind yourself: “This is the point. This is my job”. Rachel Cusk puts it much more eloquently than I could:

“Motherhood sometimes seems to me like a sort of relay race, a journey whose purpose is to pass on the baton of life, all work and heat and hurry one minute and mere panting spectatorship the next; a team enterprise in which stardom is endlessly, reconfigured, transferred”.

And while campaign planning is clearly not as demanding as either touring or parenting, we can see some similarities in its double-edged, relay race nature.

Ideas, particularly big ideas, must be robust to survive their journey from inception to reality. They need to be able to stand on their own. Agencies often rely on their clients to help ideas make their passage through the approvals jungle. Similarly, clients rely on their agencies to ensure that the idea remains true to what they approved. Both sides relinquish an element of control to see ideas thrive - otherwise, you can end up stunting their growth.

The highs and lows of campaign planning may not have anything on selling out Brixton Academy for five consecutive nights, but there are certainly similarities there. There can be exhilarating highs and often some crushing lows to navigate. But generally, no matter the outcome, we dust ourselves and go again. We get excited about ideas and the possibility that they might see the light of day. We inevitably imagine the glory moment - the award win, the kickass case study - while downplaying the potential obstacles in our mind.

And while you may not end up with the winning ticket or have your three wishes granted, you’ll probably also avoid losing any friends.