A more fluid approach to notes

Saving information for future use is eminently sensible. But could your store of information be more hindrance than help?

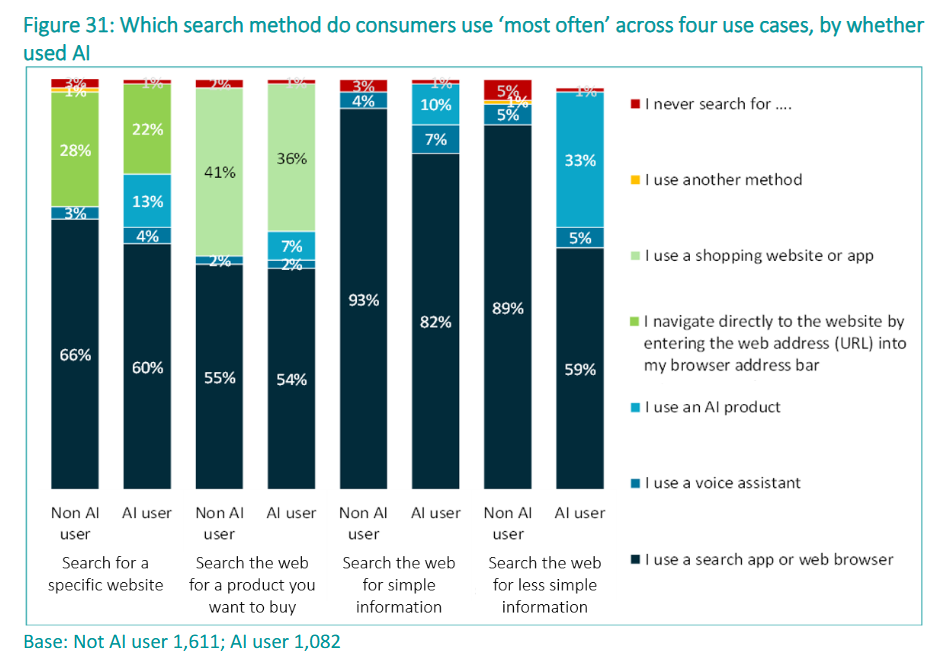

According to research conducted by the CMA as part of its investigation into the search market, 33% of “regular AI users” turn to generative AI when looking for “specific or complicated information”. That’s compared to 4% of the general public using generative AI for more general search activity.

The recent changes to Google’s search algorithms make it almost impossible to move results away from what the machine THINKS you’ve asked, no matter how much you change your search terms. GenAI tends to be more likely to find that one specific piece of information you vaguely remember but can’t find in your notes app, bookmarks or emails.

We’re desperate for the machines to get even better at these specific information retrieval tasks. How much chat or email traffic does your agency or comms team generate by asking variations of “does anyone have any examples of [x] slides they can share?”.

Providing secure access to a range of files and data points should allow a genAI tool to answer these questions much more efficiently. At Headland, we’ve tested out connecting specific SharePoint folders to ChatGPT and Copilot, and the feedback has been positive. As ever with software powered by LLMs, the results can sometimes be patchy and inconsistent, but still helpful, particularly for more straightforward requests, such as NDA templates.

The problem with outsourcing this kind of information retrieval task to a machine is that it requires the files and information to be labelled and tagged in clear and consistent ways. And in comms, our documents don’t always fit into these nice definitions.

If we put a case study in a new business presentation, we don’t always label the slide “case study” because that’s an incredibly boring title for a slide. So we might call it “Delivering killer results for Acme Corp.” or something. So, the machine has to work harder to determine that this is indeed the case study you’re looking for - or it misses it altogether.

And the task of going through hundreds or thousands of files and tagging them according to their contents is one that no human wants to undertake. This challenge highlights a disconnect between how software stores information and how we recall and access it.

We don’t tend to browse existing information or a list of files in the way that we might browse the internet or our social feeds. Our minds tend to work in a less linear fashion than that.

For

, whose excellent post “Notes are conversations across time” I stumbled back on, there’s a much more circular aspect to how we come up with ideas, and how we access the information to come up with those ideas.As Brander puts it, “creativity is a circular conversation that arrives at an unexpected destination”. This analogy works the same as if you’re riffing with other people on a topic as it does when tackling a challenge solo. Except that the conversation in that latter instance is with yourself, with your experiences, with your thoughts and ideas.

And it’s often during those conversations, whether solo or in a group, that your mind will surface some piece of information. An article you remember reading about students’ study habits from 2021. A campaign you vaguely remember from last week. A killer statistic you heard mentioned in a podcast.

The task then becomes how to find that piece of information, and often your brain won’t have stored it with the same rigour as your knowledge software. So you have to search it out.

This activity loop - have a thought, vaguely remember an example, struggle to find the example across your digital knowledge stores - might make you think about whether you have the right knowledge stores in place. It might make you think you should consolidate, or switch services, or go fully analogue with notepads and post-its galore.

However, as per this post by Joan Westenberg, perhaps you should delete it all and not bother with digital notes at all (thanks to the Storythings newsletter for bringing this post to my attention).

And while this may sound utterly terrifying (particularly to someone like me who files away a few of the newsletters I subscribe to), Westenberg’s logic is eminently sound.

She feels like her digital knowledge store is too static, “a dusty collection of old selves, old interests, old compulsions, piled on top of each other like geological strata”. It lacks the dynamism and the ability to lightly pull from what our less well-organised brains provide:

“A quote would spark an insight, I’d clip it, tag it, link it - and move on. But the insight was never lived. It was stored. Like food vacuum-sealed and never eaten, while any nutritional value slips away.”

I can certainly relate to this point. My “random stuff” Notion notebook contains a whole bunch of quotes and interesting phrases I’ve saved over time. But it’s only the ones that managed to stick somewhere in my brain that I’ve ever gone back to.

Example: The other week, I remembered that there’s a German word for the anticipation of something being more enjoyable than the thing itself. I knew I had it saved, so I went and looked it up. But flicking through that collection of quotes, while perfectly enjoyable, doesn’t tend to lead me anywhere interesting. The word is “vorfreude”, by the way.

Westenberg’s replacement for her previous “store everything” approach captures that lightness and free-flowing circularity of Branders’ conversations across time:

“My new system is, simply, no system at all. I write what I think. I delete what I don’t need. I don’t capture everything. I don’t try to. I read what I feel like. I think in conversation, in movement, in context. The important bits will find their way back.”

The important bits will find their way back - this is a mantra I live by, inspired by Salmon Labs founder Rob Estreitinho. Rob’s approach to research when developing strategy is to read everything, as much as you can, as far and as wide as you can. Immerse yourself in the world of the brief, explore the edges, and get to know the important factors.

Then, you leave that research and reading behind, and you write down what you think - an answer, an initial direction, a draft approach. Anything that’s relevant to your answer from your research, you will remember, and you can include as evidence. Anything that’s not relevant, you leave behind.

The research and the knowledge aren’t the goal. The answer, the end product, is the goal. The research is part of the circular conversation - otherwise it carries too much weight, and ends up making your answer feel flabby. Less is always more when it comes to strategy development - cut those slides back, stick the research in the appendix.

Your knowledge, your body of research you’ve accumulated over time, whether as individuals, teams or agencies, should be an active resource that you can dip into when you need. It should ideally provide inspiration, starting points or reassurance.

If that knowledge starts to hinder your work, it’s worth cutting it off and exploring alternatives. The machines have improved significantly in specific information retrieval tasks - and they will likely continue to improve. But we should still rely on our human capacity to make connections and identify patterns where they haven’t existed before. That’s something unique we can provide to any creative process.