Fissures and fractures

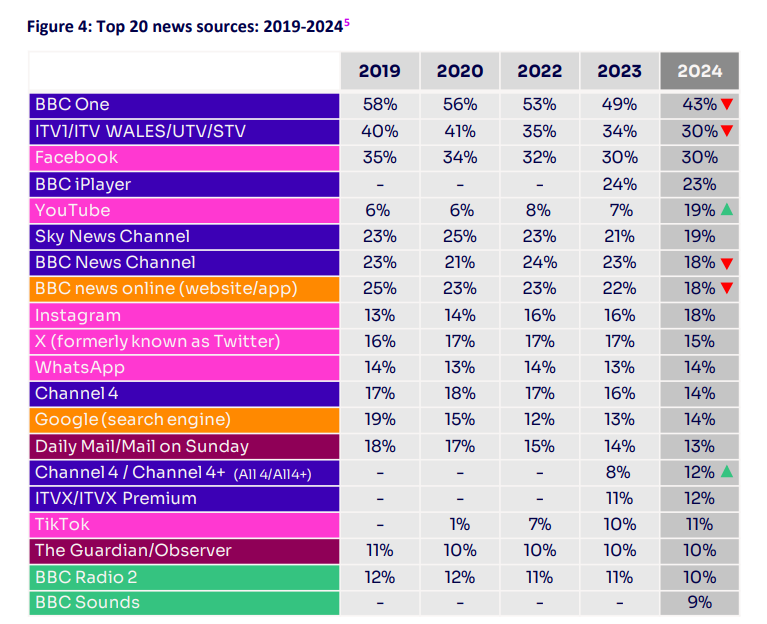

Research from Ofcom and the Reuters Institute demonstrates just how fragmented and diffuse our news consumption habits are in 2024.

TikTok for news mania swept across my LinkedIn feed last week. It felt like every other post (that wasn’t the Nike CEO’s resume) highlighted the research coming out of both the US and the UK showing the increased prevalence of the video-sharing platform in young people’s news diets.

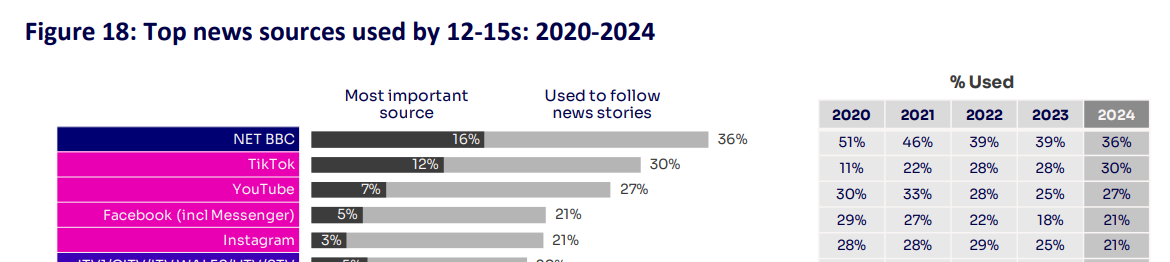

17% of American adults now get news on TikTok, a figure that jumps to 39% for 18-29 year olds. Here in the UK, 11% of the general population gets news on TikTok, with 30% of teens (12-15) doing the same. In fact, TikTok is the single most popular platform for younger teenagers in the UK:

These are precisely the kind of attention-grabbing headlines that any new piece of research needs to cut through in our cluttered media landscape. Not only do we have big numbers that agency folk like me can pop into our trend decks, but the findings also come with distinctly punk rock inter-generational conflict vibes. How can TikTok be a viable news source? It’s just kids dancing and doing crazy things with food. It’s not a serious news source like the FT.

And yes, the headlines do reinforce the need for brands and businesses to be relentlessly multichannel in how they approach communications to cut through in an increasingly fractured media environment.

And yes, planning for your ideas and stories to translate to TikTok does require you to think about those ideas through a different lens (good luck putting your research report into a 60-second vertical video).

But looking beyond the headlines of some of the recent media consumption research throws up many more questions than can be answered by “being more multichannel”.

Ofcom’s UK news consumption report highlights how this baseline increase in “news” consumption could mislead someone simply skimming the headlines.

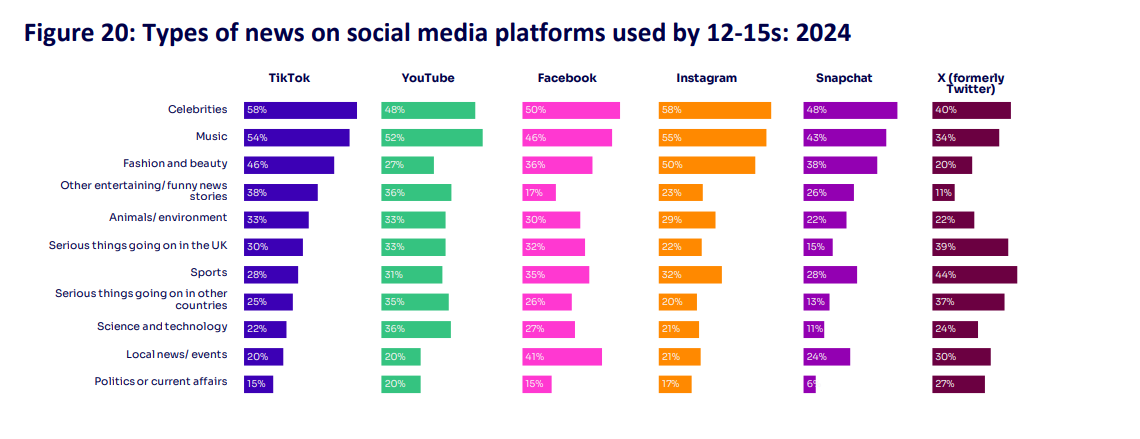

The news those teenagers consume on the likes of TikTok (and almost to an equal degree, YouTube) isn’t necessarily what we think of news when we’re coming up with campaign and story ideas. The top topics are celebrities, music, fashion and beauty and “entertaining/funny news stories”. You must scan down to the sixth most popular topic to find “serious things” on the list, with local news and politics languishing at the bottom.

It’s also the case that anyone using social media platforms to access news (not just teenagers) is most likely to discover stories via the trending topics of that platform. For the TikTok users, that, of course, means their For You page. Only 7% of TikTok users follow a traditional news organisation, although 17% follow one of the BBC’s accounts. Media organisations on TikTok are just as desperate to appear on your FYP as any other creator.

There’s also a final complicating factor in the “TikTok is the new hub for news” narrative: only 43% of people who use social media for news felt it “provided trustworthy news stories”, compared to 69% of people who use TV for news. This sense of distrust in news viewed on social media was even more acute among younger people - only 37% of 16-24-year-olds trust the stories they see in their social feeds.

So, while it is essential to plan for a variety of channels when developing campaign and story ideas, it’s not a simple box-ticking exercise. To quote Avril Lavigne, people’s relationship with “the news” is complicated.

We want to feel informed about current events to maintain our innate human connection to the world. But there’s a growing sense that the media and information ecosystem is ill-equipped to cater to different audiences’ needs when it comes to news.

Young people do want their news from their social feeds, but either distrust what they see or feel the stories aren’t relevant to their interests.

TV news remains the closest thing to a trusted news source, particularly the BBC One nightly news bulletin. However, a linear nightly news bulletin is ill-equipped to cater for modern media habits.

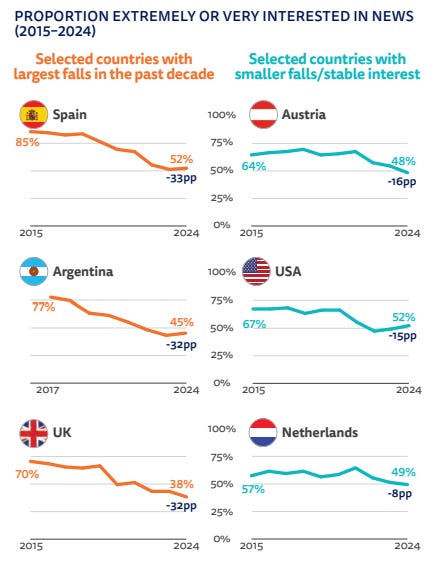

There’s also the overlaying factor that the bleak feeling nature of our current news cycle is too much for many people. This year’s Reuters Institute Digital News Report reports that selective news avoidance increased again by 3% on average globally to 39%.

The ongoing conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East play a role in this news avoidance, alongside a general sense that there is simply too much news. The Reuters Institute study also identifies another generational gap in the types of news people want to read. Under 34s are much less interested in politics globally, preferring to see stories about the environment and climate change.

Overlaying the key findings from both Ofcom and the Reuters Institute highlights some of the fissures and fractures within the current media ecosystem. And these fissures and fractures have created expectation gaps between what people want from their news and what they actually receive.

The overriding sense is that people want to receive their news on the platforms they use the most - whether that’s social, search or more direct relationships with publishers. People enjoy the convenience of having their news curated for them, most commonly by algorithms, but can also feel bombarded by both the volume of news, and stories which feel depressing or irrelevant.

Young people especially distrust what they see in their feeds, feeling that it lacks the rigour of the more traditional news sources that they’re aware of but don’t engage with. There is also a generational divide around the very concept of news itself. Younger people see news as synonymous with entertainment; for older people, news remains harder-edged and more political.

These tensions and divides in our news consumption habits point to a media ecosystem whose cracks and fractures are becoming more stark every year.

It may be that these fractures and fissures only exist because both Ofcom and the Reuters Institute try to study “news” in totality, as one singular concept. Any form of news, from the earliest newspapers to the latest generation of TikTok newshounds, is multifaceted. There’s always an element of human curation based on your interests. You choose the section of the paper you flick to or which videos to watch in your feed.

So, by starting all our campaign planning and story generation with specific target audiences in mind, we may be able to deftly circumnavigate the tricky relationship “people” have with “news”. We can take advantage of the rise in younger people using TikTok for news by being granular in who we want to target (young people is an awfully vague term) and understanding precisely what it is those audiences look for in their feeds that relates to their notion of news.

Additionally, one of the defining trends of 2024 is the sense that there is no longer a centre of gravity for collective online conversation. And given that the news agenda has a symbiotic relationship with online conversation, it’s no surprise that we’re seeing this same fragmentation across the media ecosystem.

The difference with our media ecosystem is that, at least for the time being, macro stories still dominate the news agenda. The Labour Party conference will have been a constant across your news feeds this week, alongside the Gaza conflict and election success for the far right in Austria and Germany. However, given young people’s desire for “entertainment-style” news and the broader news avoidance trend, it would be no surprise to see someone soon try to carve a niche for themselves with “news that gives good vibes only” (or something similar).

No matter how the future of news and our media ecosystem plays out, brands and businesses must prepare to reflect the current fragmented landscape in campaign planning and idea generation.

That means having a clear and detailed understanding of your target audience and their media consumption habits.

That means thinking about how to make those campaigns and stories work across various channels.

And it means having a plan to measure the impact of those campaigns and stories over time, so that you can continue to iterate and improve over time.

It’s easy to get excited about people consuming more news than ever on TikTok and to see this as a gateway to a bridge future for the media. But the research highlights underlying fissures and fractures that show few signs of healing in the near future. That means it will take careful consideration for brands and businesses to cut in an increasingly cluttered, complex and fragmented media landscape. We mustn’t let the hype and the headlines distract from the rigorous planning task at hand.